Give Birth, Nurture, Grieve: a Gredos Wet-nurse and a Madrid Foundling, mid-19th Century

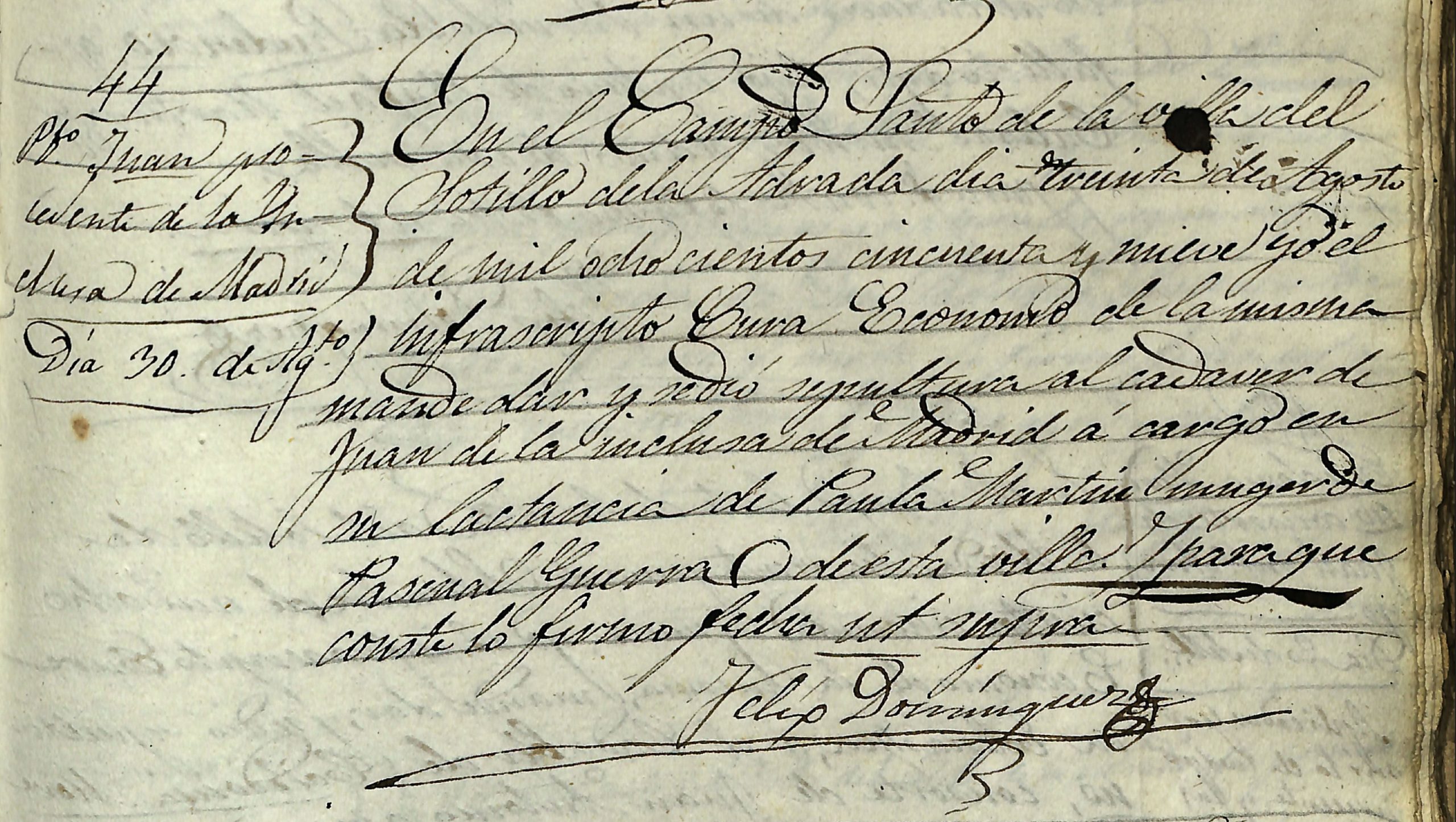

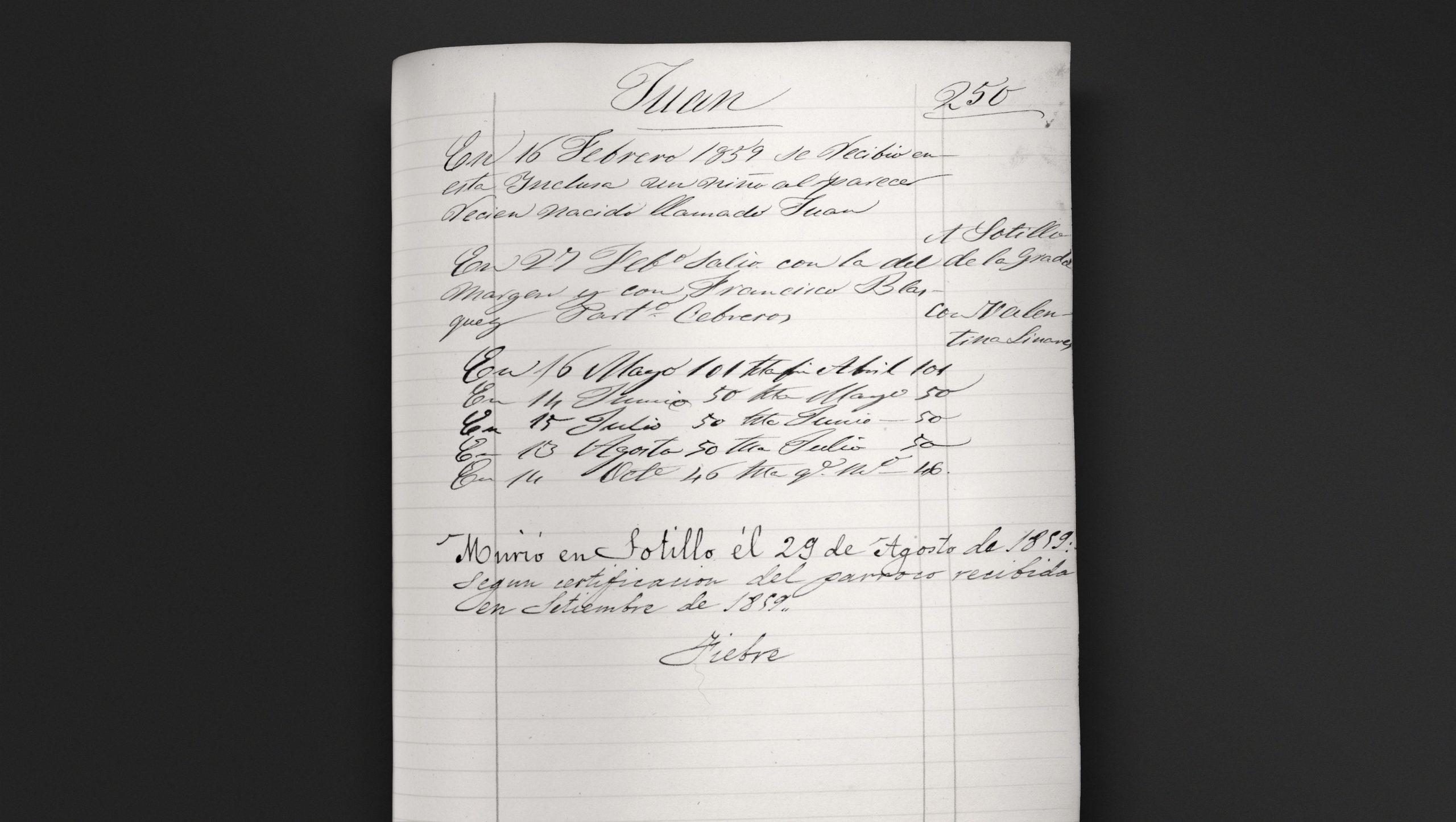

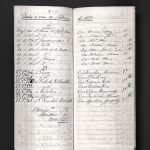

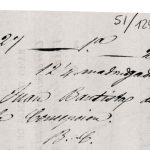

In memory of my great-aunt Marie Hainzl, born in a small village, died in Vienna

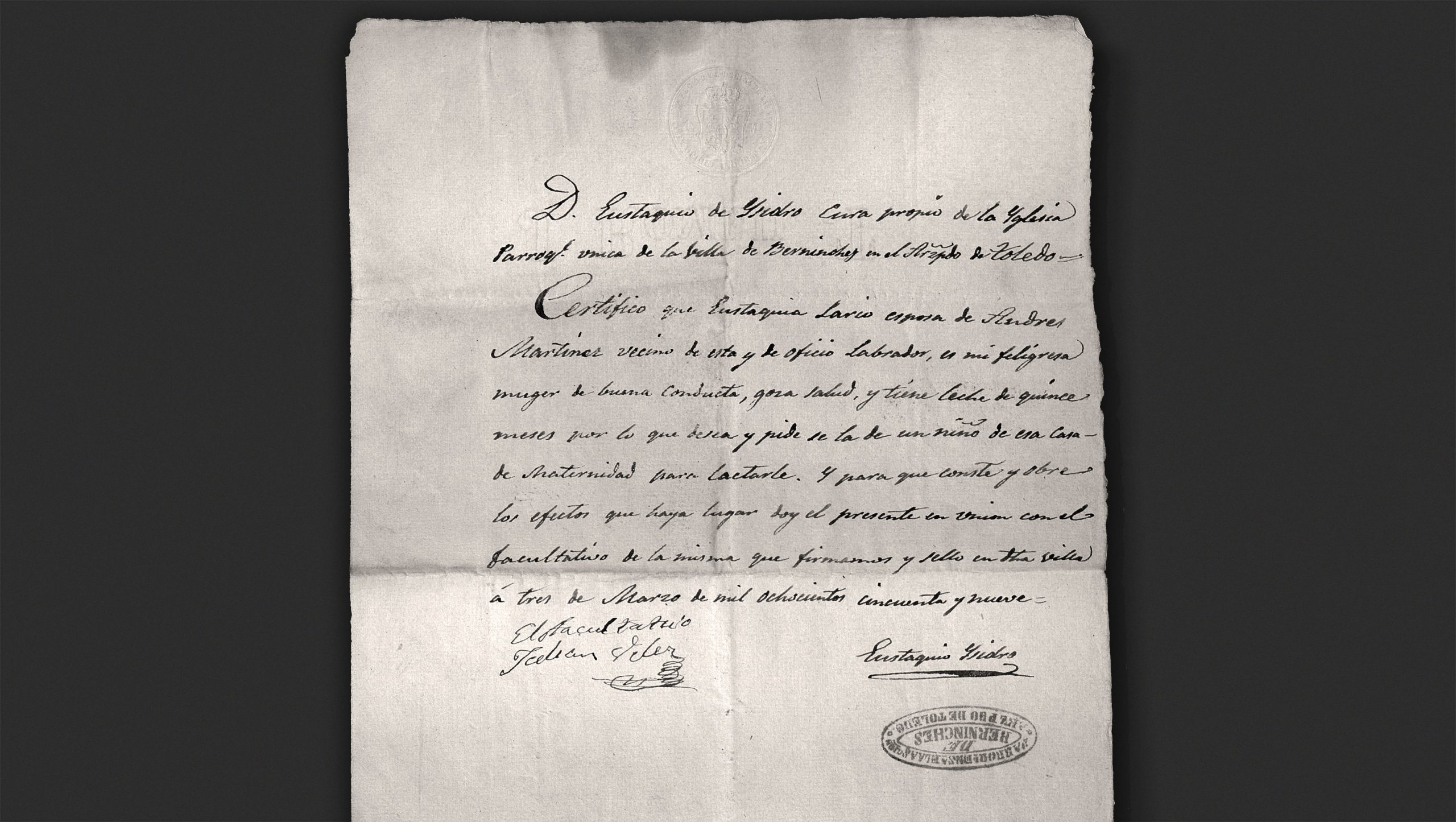

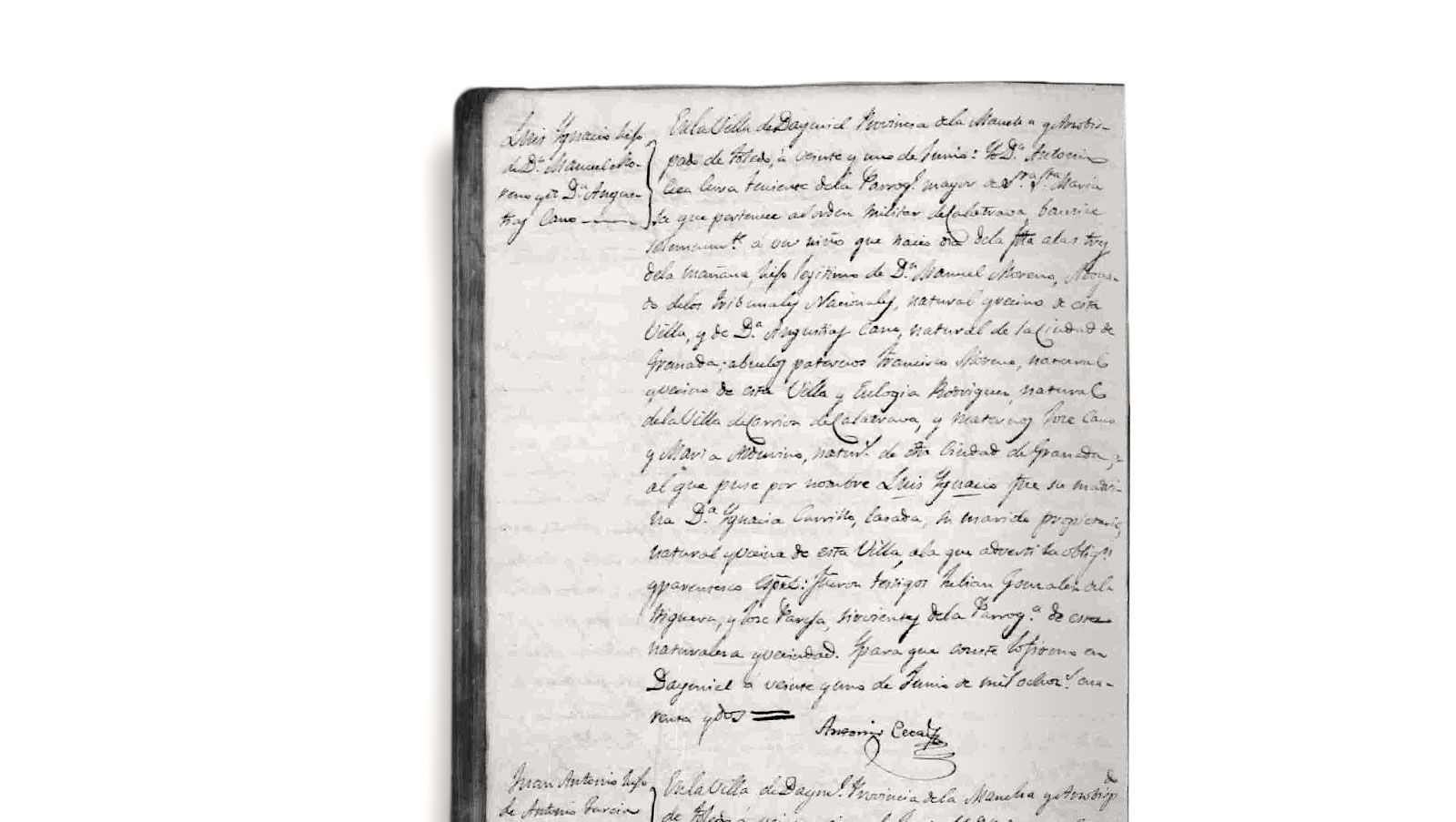

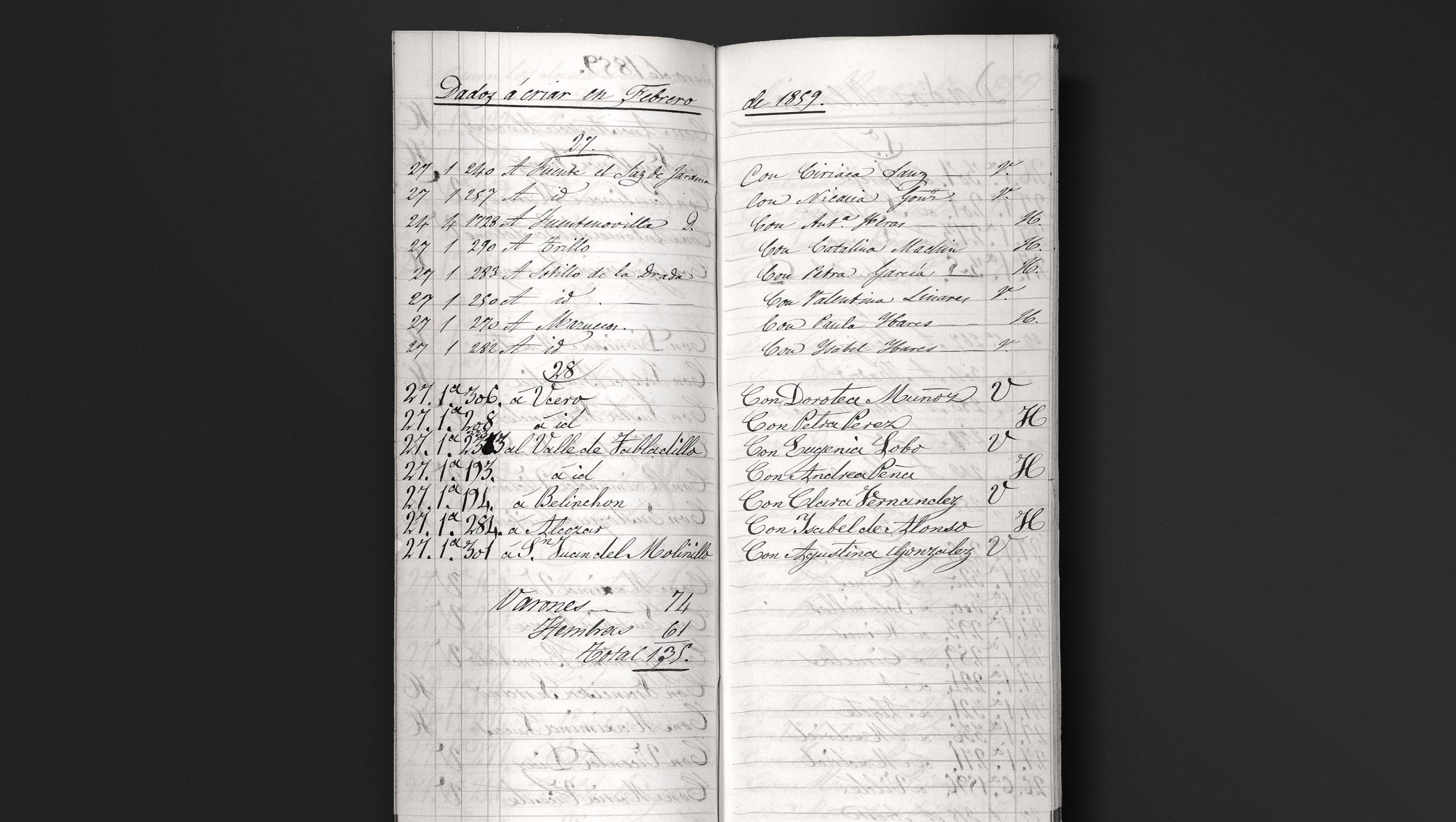

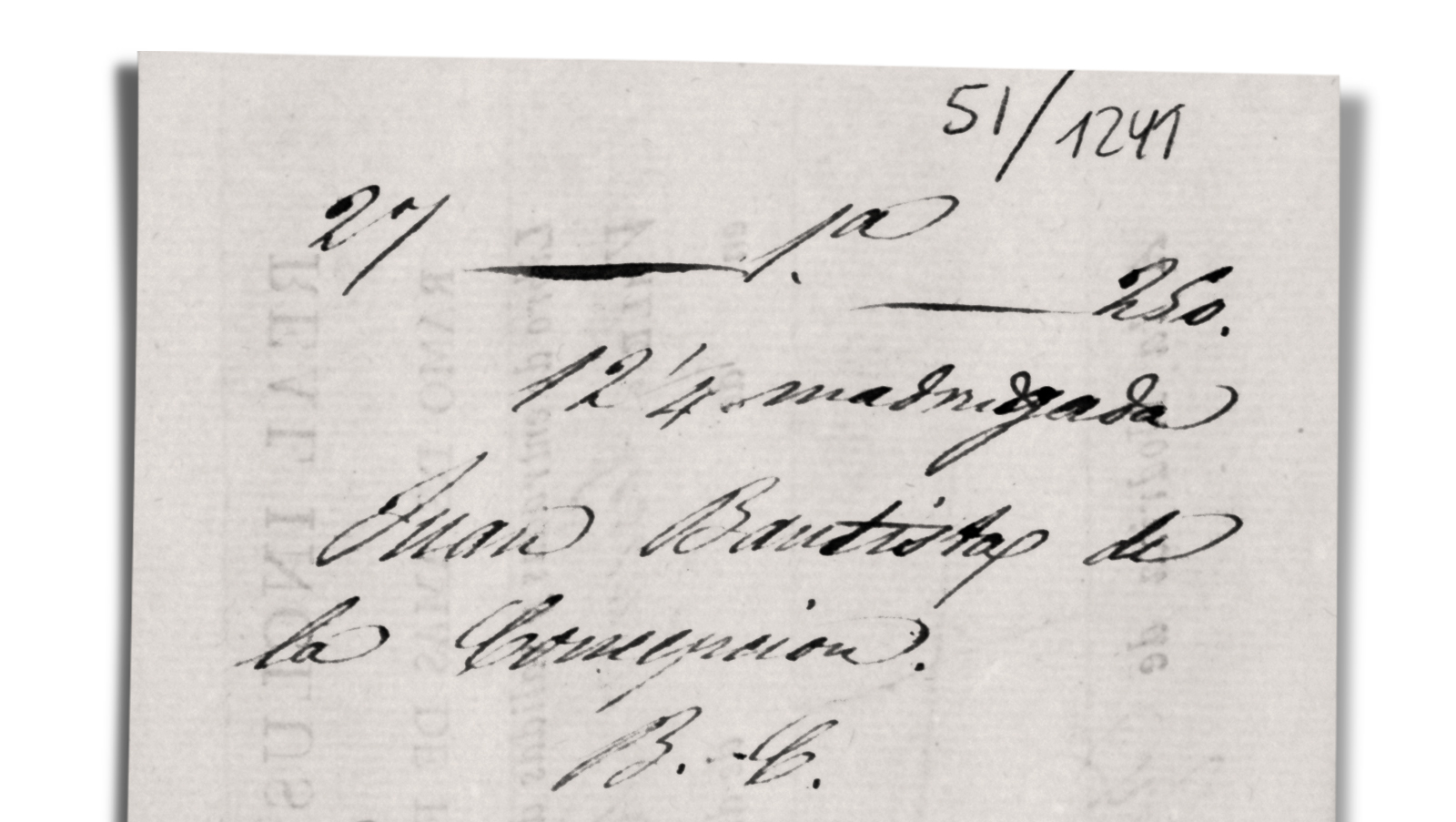

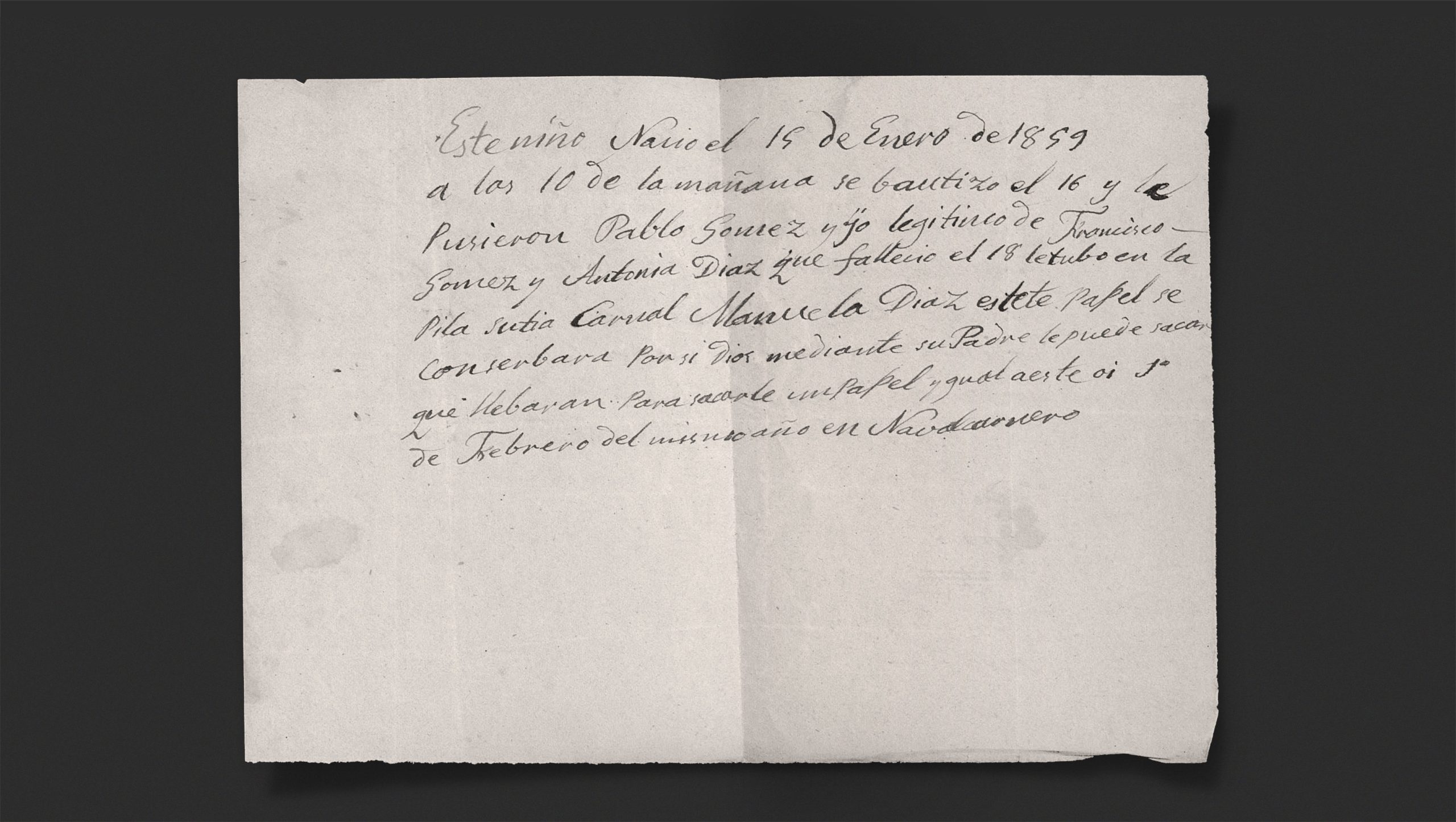

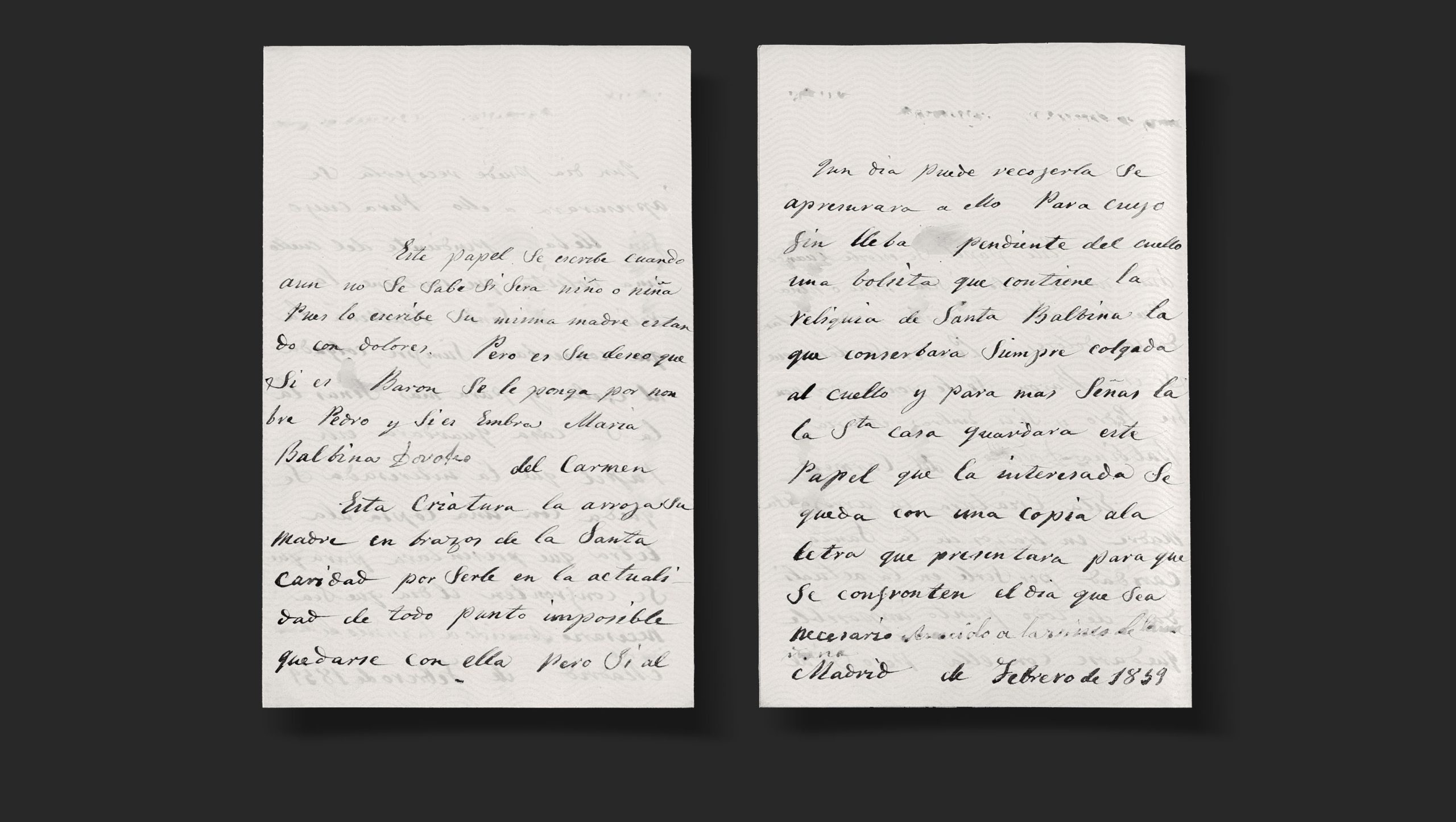

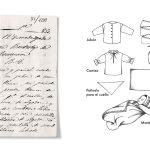

In the spring and summer of 1859, the paths crossed of Juan, a newborn from the “Inclusa” foundling hospital in Madrid, and of a village woman from the Gredos mountains. It would only be short-lived, this encounter between the inclusero and the wet-nurse engaged by beneficence. The archives of the Inclusa and of the diocese of Ávila contain only a few documents relating to the event, records holding just one or two small signs, a handful of tantalising pointers towards a wider historical and social context: a couple of dates marking a life’s beginning, and also its end; some names and familial connections; a couple of social clues drawn from how the baby was clothed prior to its exposure on a winter’s night in Madrid; the pecuniary value of a wet-nurse’s milk; the cause of an infant’s death as certified by a rural physician.

These details allow us to imagine and sketch out potential scenarios of family life at the time, and of the first days of infancy. They prompt the scholar to reflect on the ways the historical context dictated how some of humanity’s great existential challenges would be confronted here: a baby’s defencelessness; the nurturing a newborn so desperately needs and may be given; maternal attentions portioned out between children and siblings; the bond created between infants fed at the same breast… and finally the female body, and its ability to bring new life into being. In this latter case we then ask the question so often posed in myth, novels and tragedies: what happens when the mother is absent?

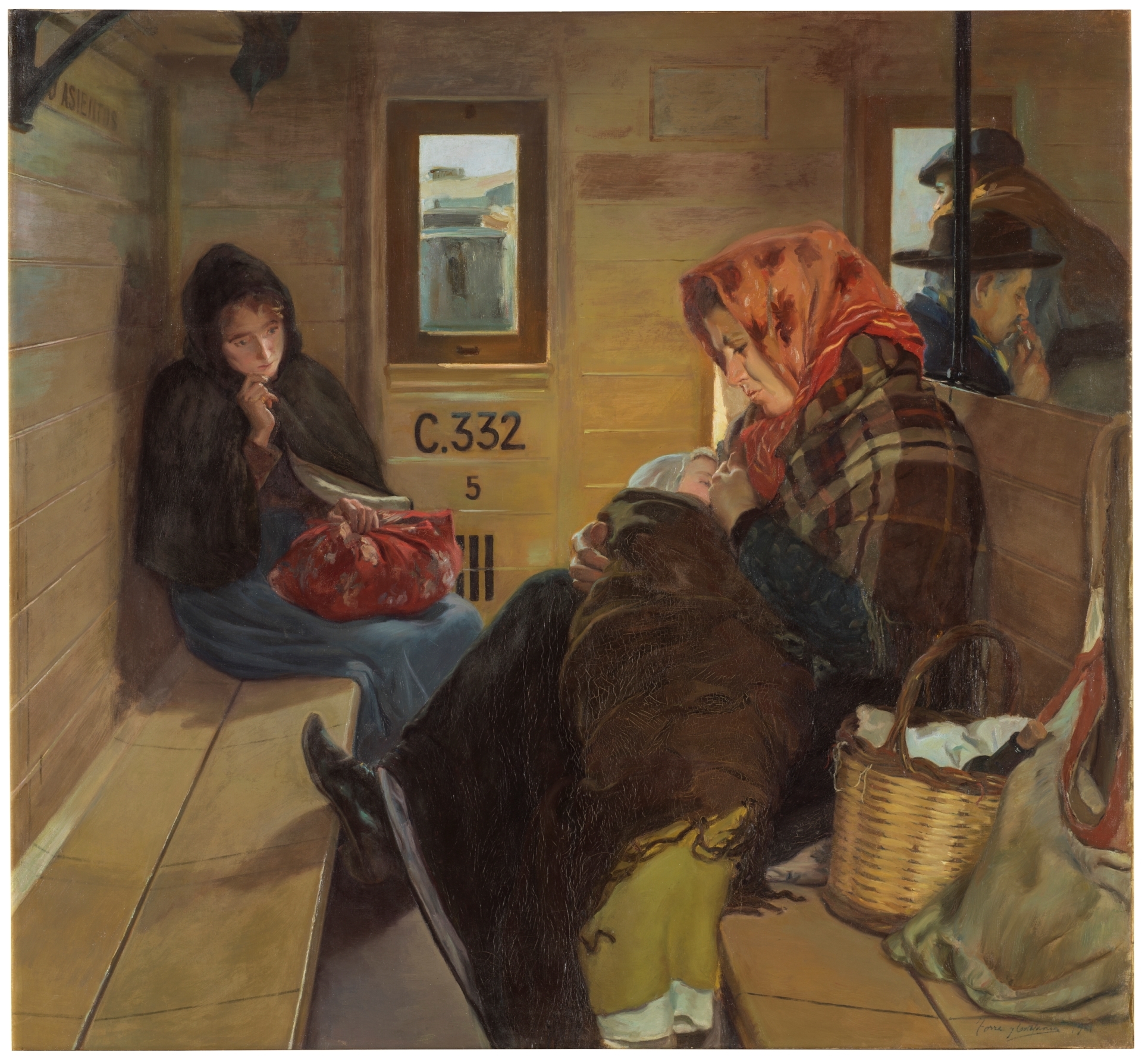

We find ourselves in the period of recovery and economic expansion that took place during the reign of Isabel II and her dynamic prime minister Leopoldo O’Donnell. The capital was growing, up from two hundred thousand inhabitants in 1850 to two hundred and eighty thousand in 1859. The city no longer felt so disconnected from the mountain valleys, as men and women from the villages arrived in great numbers to work: in the shops, as craftsmen, in the tobacco factory, or to serve in fine houses – and also to labour in the washing-places or the Madrid taverns and cabarets. Alternatively, some of them could offer their services as wet-nurses: and every day the papers carried commercial advertisements offering and seeking mother’s milk. This is the period so expertly related to us by the contemporary novelist Benito Pérez Galdós.

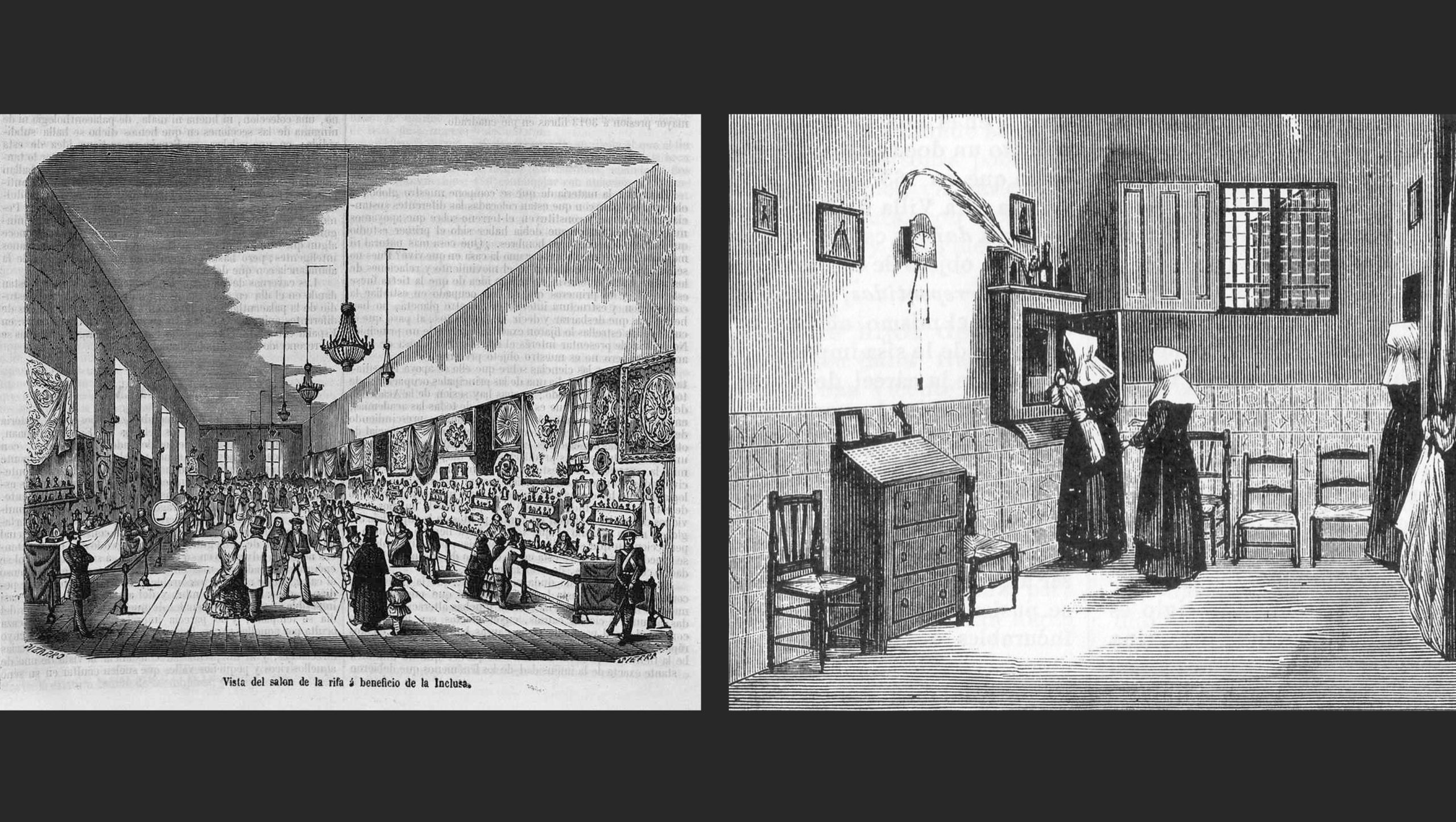

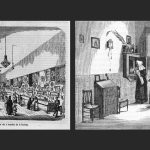

Each night, the Madrid Inclusa in Mesón de Paredes street – in a building now demolished, on a hill in the modest Lavapiés neighbourhood – took in some half dozen foundlings. These were often boys and girls transferred from the Casa de Maternidad, the hospital where their mothers had gone to give birth to them without revealing their identity. Others would have been collected from a doorway or street corner by the Santa Hermandad del Refugio, an order devoted to this pious mission. And in other cases, the infants would have been placed directly in the foundling wheel in the Inclusa itself, or in another of the revolving mechanisms dotted around Madrid, where they could be left without the depositor fearing recognition.

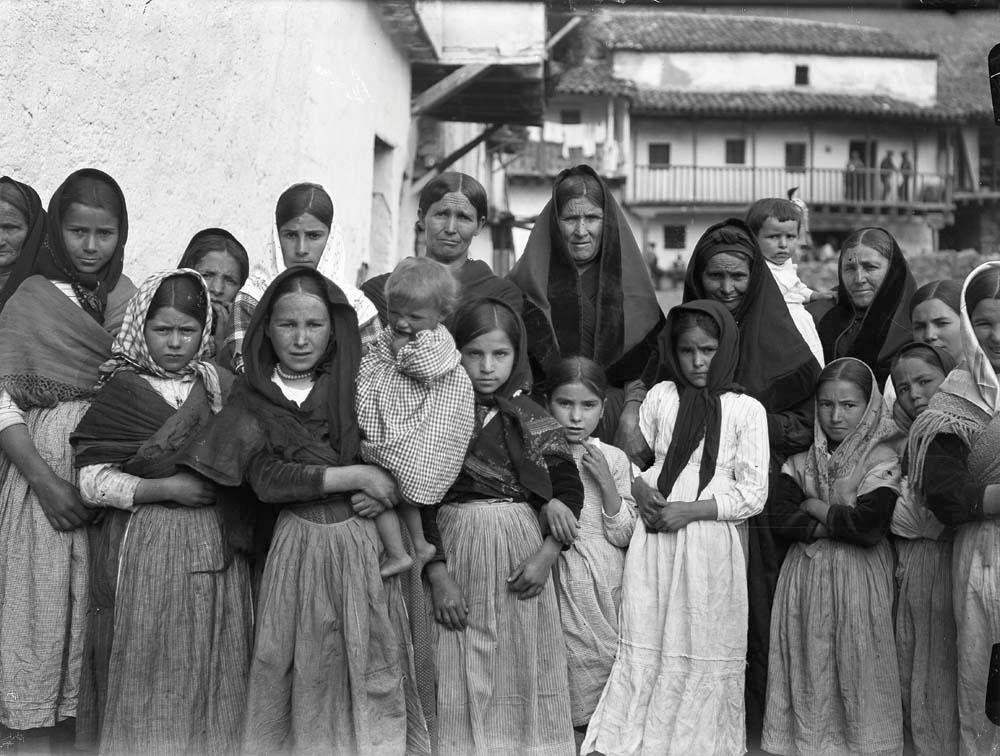

And every day several women from the villages of Castile – duly furnished with a certificate of suitability from the local priest or physician – would present themselves at the doors of the Inclusa and apply for a child to take back to their homes to nurse. They would come from the provinces of Madrid or Guadalajara, mostly, but also and increasingly from Toledo, Ávila, Segovia, Soria or Cuenca. These rural wet-nurses would be mothers in their own right, often of several children, a few perhaps mourning a lost baby, some already feeding a baby of their own, or others the mothers of children just weaned.

We find ourselves, then, before two discrete, unique realities of this period: one the exposure of foundlings, and the other life in the rural villages generally considered to be altogether cut off from the city. It is remarkable to see how these two distinct phenomena would then merge into a social mechanism of “imperfections, admirably balanced and combined”, as described by Galdós in his novel Fortunata and Jacinta. Two of the most striking features of this blended system were a disquieting cruelty towards the most vulnerable, and an appalling infant mortality rate.

We will therefore approach our subject from a perspective which connects two different social wholes, the rural and the urban. Taking this angle should shield us from certain tired tropes which, while not usually present in academic scholarship, abound in popular historical accounts. These are the supposed isolation of the rural villages, which were therefore unable to participate in the complex process of modernisation; the absence of women from “work” prior to the 20th century; and poverty as the factor underlying (almost) everything.

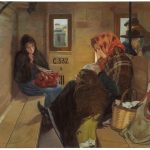

It is not easy to present this subject in an attractive, accessible way for a digital audience accustomed to visual content, since it was unusual to take photographs of the interiors of rural dwellings, and neither were many illustrations made of life inside the Madrid Inclusa or other Casas Cuna (foundling hospitals) before 1900. Wishing to avoid the risk of giving a potentially anachronic impression, we have largely eschewed the use of images from periods later than the one discussed here, preferring to let the texts speak for themselves. It may just be that the very concision of the written records – with their language choices so revealing of contemporary attitudes – ultimately excites the historical imagination more than any visualisation not anchored in the period described could ever do.

There is only a small number of sources which facilitate detailed study of confinements and early infancy in the homes of the common people of the time. It is on account of this, and with great reluctance on our part as historians of childbirth, that we had no alternative but to make use of records from society’s elites, accounts of babies born in royal palaces and the great houses of aristocrats. This makes it a challenge to avoid hierarchical bias – a shortcoming we were conscious of in our earlier work on this subject, published in 2022. Since then, however, we have learnt a little more about the confinements of our grandmothers and great-grandmothers, having discovered how much relevant information is contained in two magnificent new sources, easily consulted thanks to Family Search and other databases, and packed with surprises for the scholar who immerses herself in their extensive archives. These are the parish records, for one, and secondly the archives of the Casas Cuna. We will share many examples here, in the hope of awakening our readers’ curiosity, and invite them to add new brush-strokes to the ever-enigmatic painting of the past.

Curator: Wolfram Aichinger, professor and researcher at the University of Vienna. Also under his coordination, the 2022 Double Temporary Exhibition Cultures of Birth in Early Modern Spain and Europe can be visited at the Virtual Museum of Human Ecology.

Contribution

With contributions from Wolfram Aichinger (Universidad de Viena), Jesús Caramanzana (Producciones Carrera), Lara Carasa (Universidad de Navarra), José Antonio Fernández Fernández (Universidad Rey Juan Carlos), Hannah Fischer (Universidad de Viena), Sabrina Grohsebner (Universidad de Viena), Lisa Heilig (Universidad de Viena), Anna Sophie Herrnhofer (Universidad de Viena), Karolina Kaniewska (Universidad de Viena), Flora Menslin (Universidad de Viena), Pilar Panero García (Universidad de Valladolid), Walburga Plunger (Universidad de Hildesheim), Barbara Rytsk (Universidad de Viena), Fernando Sanz-Lázaro (Universidad de Viena), Carlos Varea (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid) y Sophie Winklehner (Universidad de Viena).

Abigail González (Universidad de Viena) y Tamara Hanus (Universidad de Viena) prepared the pictures.

Fernando Sanz-Lázaro edited the Spanish version of the texts, John Wright translated from Spanish to English.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the following for their inestimable assistance: Valentín Carrasco González (Sociedad de Estudios del Valle del Tiétar), Julio Sánchez Gil (Real Academia de Bellas Artes y Ciencias Históricas de Toledo), Javier Abad (Sociedad de Estudios del Valle del Tiétar) for speaking with us about the incluseros of the Valle del Tiétar and for sharing photographs of the time; to Victoria Manzanas Bardera for discussing the incluseros of Almendral de la Cañada around the mid-20th century, to Macià Tomàs-Salvà (Real Academia de Medicina de las Islas Baleares) and Gabriel Janer Manila for clarifications on the matter of “leche preñada”, to Rafael M. Pérez García for bringing the paintings from the Casa Cuna de Sevilla to our attention, to the parish of Sotillo de la Adrada, to Blanca I. Bazaco Palacios, Nieves Sobrino, Ángel González and all the remaining staff at the Regional Archive of the Autonomous Community of Madrid for their extraordinary support and for resolving acronyms; to John de Blas Bragado García, archivist, and José Antonio Calvo Gómez, director, of the Diocesan Archive of Ávila for their courteous and prompt attention. We are also indebted to Bettina Geisselmann, coordinator of the Re_hacer project, Néxodos collective, for providing photographs of nipple shields and describing the mothers who used them. Equally, we express our gratitude to the council of the Santa Iglesia Metropolitana of Burgos for permitting access to the Santa Casilda de Briviesca sanctuary.

A special message of gratitude must go to José María Yáñez Sinovas for his detailed and highly knowledgeable comments on the subject of the contemporary rural economy and communication networks, along with other questions of social history in the province of Ávila.

It was only possible for us to undertake this project thanks to the research initiative The Interpretation of Childbirth in Early Modern Spain II, subsidised by the FWF Austrian Science Fund (https://doi.org/10.55776/PAT2471824), a part of wider research by LVCINA. Sociedad Española de Historia del Nacimiento.

We are also grateful to SEVAT Sociedad de Estudios del Valle del Tiétar for all the hospitality shown to us in Lanzahíta in the summer of 2025.

Further reading:

Abad J. 2024. Los niños expósitos en la provincia de Ávila en el siglo XX . Avisos de Viena, 9: 13-30.

Aichinger W. 2024. ¿Lo que más temían las mujeres? Partos mortales y embarazos de riesgo en palacio y en casas de pobres (Siglo de Oro con incursiones contemporáneas). Avisos de Viena 6: 53-66.

Aichinger W. 2023. Los bautizados de socorro de Pedro Bernardo (Ávila). Un momento de transición en el registro de la muerte neonatal. Memoria y civilización 26.1 (2023): 231-253.

Aichinger W. 2021. Parentesco breve: El inclusero Juan y su nodriza Paula Martín (Marzo a agosto 1859: Madrid y Sotillo de la Adrada). Avisos de Viena, 4: 149-171.

Aichinger W, Grohsebner S. 2025. Childbirth in Early Modern Spain. Wiener philologisch-kulturwissenschaftliche Studien | Vienna Philological and Cultural Studies, 3.

Aichinger W. 2021. Grandmothers reborn: Allomaternal care as an uncharted territory of Spanish History. Avisos de Viena, 2: 12-25.

Aichinger, W. 2021. Enfants et rires, richesse de pauvres: Un ama de cría le canta las cuarenta al Rey Felipe IV de España. Avisos de Viena, 2: 7-11.

Aichinger W, Grohsebner S. 2025. Childbirth in early modern Spain, Praesens.

Aichinger W, Plunger W. 2025. Grandmother, Birth Assistant, Godmother. Grandparents and Newborns in a Spanish Mountain Village (Pedro Bernardo, Ávila, 1850-1861). Memoria y Civilización, 28.1: 211-240.

Bernis B, Varea C. 2012. Hour of birth and birth assistance: from the Primate to a medicalized pattern? American Journal of Human Biology, 24: 14-21.

Biblioteca Nacional de España. Hemeroteca Digital. Diario oficial de avisos de Madrid. https://hemerotecadigital.bne.es

Cantón de Salazar J. 1734. El pasmo de caridad y prodigio de Toledo. Vida y milagros de santa Casilda. Viuda de Juan de Viary.

Carrasco V. 2025. Comarca de Sierra de San Vicente: tierra de acogida de niños de la Inclusa de Madrid, Aguasal, 86: 16-17.

Domínguez Moreno JM. 1988. La lactancia en la alta Extremadura. Revista de folklore, 89: 147-157.

Espina Pérez P. 2005. Historia de la Inclusa de Madrid. Vista a través de los artículos y trabajos históricos. Defensor del Menor en la Comunidad de Madrid.

Fernández Fernández JA. 2020. Pañales y mantillos de los infantes de la Casa de Austria (1545-1661). Hipogrifo, 8.2: 635 – 664.

Freire Paz. Elena. 2004. La recuperación de la alfarería tradicional en la provincia de Lugo: procesos socioeconómicos y culturales. Tesis doctoral, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela.

González López T. 2020. Creencias, asistencia y nacimiento. Dar a luz en el interior de Galicia (ss. XVII-XIX). Investigaciones históricas. Época moderna y contemporánea, 40: 295-314.

González Pérez P. 1987. La cerámica preindustrial en la provincia de Valladolid. Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Valladolid.

Hrdy SB. 1999. Mother nature. Chatto & Windus.

Knodel JE. 2002. Demographic behavior in the past: A study of fourteen German village populations in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Cambridge University Press.

Monlau y Roca FP. 1850. Madrid en la mano. Imp. de Gaspar y Roig.

Morel M-F. 2021. Morts des méres, morts des nouveau-nés: histoire et représentations (xvi e-xx e siècle). La naissance au risque de la mort. Eres, 15-48.

Panero P. 2022. Pobreza, lactancia solidaria y milagros en unos exempla del s. XVIII. Avisos de Viena, 3: 85-95.

Rodríguez Martín A. M. 2019. Las madres de los expósitos en España en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. Atlánticas – Revista Internacional de Estudios Feministas, 4,1: 240-264.

Ruiz-Berdún D. 2022. Historia de las matronas en España, Guadalmazán.

Sánchez Gil J, Fernández Jiménez C. 2024. Colección de fotos familia García-Blanco y Navamorcuende, Ayuntamiento de Navamorcuende.

Sarasúa C. 2021. Las nodrizas de las inclusas de Madrid y la Mancha:(1700-1900). Salarios que la ciudad paga al campo: las nodrizas de las inclusas en los siglos XVIII y XIX: 265-303.

Todd E. 2019. Lineages of modernity: a history of humanity from the stone age to Homo americanus. John Wiley & Sons.

Torrents, Á. 1992. Actitudes públicas, actitudes privadas. 1610-1935. Revista de Demografía Histórica-Journal of Iberoamerican Population Studies 10.1: 7-30.

Usunáriz JM. 2024. Milagros y partos peligrosos en las hagiografías de los siglos XVI y XVII: Una aproximación a las causas de la muerte materna en el Siglo de Oro español. Avisos de Viena 6: 41-52.

Varea C, Fernández-Cerezo S. 2014. Revisiting the daily human birth pattern: time of delivery at Casa de Maternidad in Madrid (1887-1892). American Journal of Human Biology, 26: 707-709.

Varea C, Carasa L, Planesas P, Aichinger W. 2023. Hora del parto en Daimiel (Ciudad Real) en la primera mitad del siglo XIX. Avisos de Viena, núm. 5, 7, P 32263-G30

Yáñez Sinovas JM. 1998. Sotillo de la Adrada en 1752. El Catastro de Ensenada: Respuestas generales. Trasierra, 3: 31-46.

Further studies on the subject can be found in the bibliographies of these works, on the website of our research project The Interpretation of Childbirth in Early Modern Spain II, and in the digital journal Avisos de Viena. Viennese Cultural Studies.