Cultures of Birth in Early Modern Spain and Europe

A Cultural History of Birth

To study childbirth means tackling the complicated problem of body and mind, and material and symbolic cultures.

There is nothing more evident than pregnancy, much to the disgrace of unmarried girls of days of old who could not hide it and so suffered the ostracism of their mean communities. There is nothing more palpable than a newborn child which loudly claims its rights, apart from milk and human warmth. Birth asks for practical knowledge, about plants, potions, the use of instruments and, since time immemorial, demands the skilful hands of another woman who comes to the rescue of the childbearing one, facilitating the passage of the baby into the world. Midwives could not (cannot) be soft and squeamish, on the contrary: they were demanded to be strong and able to stay calm in scenarios of blood, surgical interventions, abortions, and stillborn babies.

Birth has its undeniably material aspects. However, all times and cultures (even our own one, ruled by machines) were well aware that birth is a process among living beings; therefore, its mental and psychological aspects are of prime importance. In Golden Age Spain, a good midwife was asked to be cheerful, understanding, optimistic, and, above all, to be good with words and to know how to tell stories in a persuasive way. When parturition lasted too long, says the Spanish doctor Juan Ruices de Fontecha en 1606, the midwife should keep telling «exemplary stories about happy endings, involving poor women as well as rich ones, slim, healthy, and ill ones, who delivered very well, although the process stopped in the middle, [...] about women, who after long deliveries bore delightful, strong babies, for this story-telling might do a lot to the case […].».

There is a third dimension to be added to the bodily and the psychological ones: the dimension of culture. What is at stake at childbirth is the future of a family, the perspectives of a clan, a community, even a kingdom. Birth brings about the renovation of human coexistence, the integration of a new member (sometimes two or three) into a social group, along with the readjustments such an addition always demands. No wonder, therefore, that, starting with conception or even earlier, pregnancy and birth are interpreted in the light of cultural values.

Birth is about bringing a baby into the world, sure enough, but in the background there always looms the big questions: What is life? From which moment can life be considered human? Who will have to provide for the newborn human being? What is the relationship between the living and the dead? What are the primordial human relations: maternal, paternal, or fraternal ones, to other kin, to a grandmother or a nurse? Through which rites should a child to be introduced into its family, parish, the faith of its ancestors? How are cultural and religious identities to be constructed? (Baptism and Christian names are powerful symbols in this process of creating cultural bonds).

Thus, from its first phases onwards, procreation is endowed with symbolism, and it is experienced through objects and acts charged with cultural meaning. (Whoever has had the good fortune to be present in a room where a baby was born, knows this perfectly well: there is no gesture, there is hardly a word spoken that does not become meaningful and later part of a collective memory shared at anniversaries and birthdays.) Birth leaves a long-lasting imprint on our lives: it initiates our most happy and most painful memories, it creates anecdotes and stories.

Thus, by studying birth we inevitably end up studying the whole culture of a society, all the details and all the shades of its features, the paradoxes, dilemmas and contradictions carved into it, its visible aspects and its hidden folds.

Traces of past experience

An exhibition is bound to remove objects and images from their original context and to abstract them from the flow of life. Great misunderstandings can ensue from that, and museums always take the risk of being perceived as mere cabinets of curiosities. Amulets and protective signs worn by pregnant women could seem strange to us, rosaries, relics and stamps of Virgins and saints as absurd manifestations created by people who, for want of better means, took refuge in magic and superstition.

To avoid these errors, it is worthwhile recalling some of the teachings of the great anthropologist Mary Douglas concerning the importance of ritual and of symbolic action: ritual synchronizes the behaviour of a social group, it focuses the attention of its members towards shared objectives; ritual creates a frame in time and space which distinguishes what is important, what is included and relevant, from that which is unimportant and therefore excluded from the frame. During rituals basic scripts and stories of a culture are recalled, those which condition the vision of life and even provide models of conduct. Ritual guides our interpretation of the world and consequently provides guidelines for action.

Our exhibition

We want to highlight five characteristics of Golden Age birth:

Firstly: In the age we are dealing with, life is felt to burst forth everywhere. Everybody is concerned in one way or another by pregnancies, abortions, miscarriages, and deliveries; by children who receive emergency baptism; by children who are baptized solemnly, or by children taken in through the baby flap of a foundling home.

Fertility is an ubiquitous concern, not only of women with child or of women who visit a holy shrine to cure their “sterility”, but of fathers, grandmothers, nuns, jurists, ambassadors, mums of queens and kings, all of whom are involved in birth. Diaries and letters from the age testify to this.

Second: Children were born into a world of coffins and shrouds. When people loved, conceived, gave birth, and raised children, it was always in a bid to counterbalance death.

Consequently, newborn babies were welcomed while memories of the dead were fresh. Every birth was conceived as a cyclical renovation of life. Quite a few babies were named after their grandparents, even more so if they had died on a date close to a grandchild’s birth.

Third: Women kept the secrets of birth to themselves. Above we have pointed out that birth was perceived everywhere —in its preliminaries, its effects, and secondary actions, be it the bells which «tolled for midwife », the presence of these very midwives in the streets at night, the screams of a delivering woman which resonated in a house or on a street, or the neighbours who came together to congratulate the proud parents. But this omnipresence of birth was only one side of the medal. The other was a sphere of well-guarded female intimacy into which only trusted women could penetrate, and, in the case of an emergency, the odd surgeon or doctor.

Fourth: It is the midwife who best knows the body and bodily cycles of a woman in her fertile years. She can detect first signs of pregnancy. She can even judge the potential fertility of a girl who has not conceived yet. She accompanies the evolution of pregnancy and gives it a first evaluation concerning the fitness of a newborn baby. Her power stems from that privileged knowledge and her possible collaboration in secret and illicit procedures. On the other hand, her testimony can be of great weight in a criminal case, and she can turn into an extended arm of political and religious authorities: In the decades which preceded the expulsion of the Spanish Morisco (in the year 1609), governments imposed Christian midwives on Morisco communities, to exercise tight control over births and baptisms.

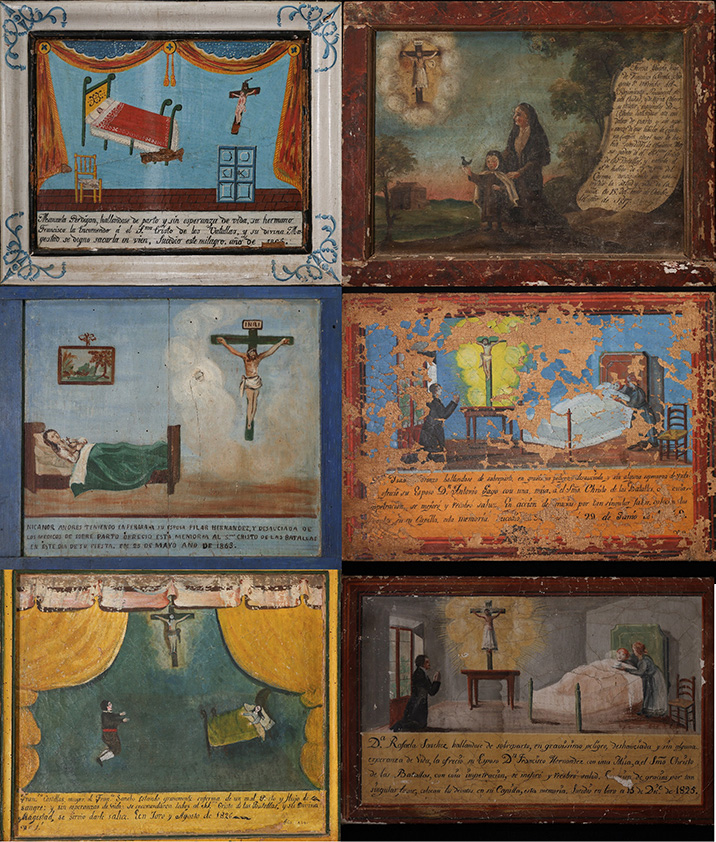

Fifth: For all these reasons, birth is not a biological fact, embellished with some religious elements. On the contrary, in Golden Age Spain, it is an event completely suffused with religious meaning, interpreted according to the faith of the time, according to the imagined link between mortals and the realm of heaven. To give birth means copying and continuing the work of God, a creature is sent by heaven and born a second time through baptism. When a baby dies, it is believed to immediately rise to heaven as an angel and to become a potent intercessor before God. Ultimately, death is a birth into the afterlife. It is no surprise that the presence of priests, nuns, or women with a reputation of saintly life were most welcome in a delivery chamber. Their advice was listened to when human means threatened to fail. Teresa de Jesus’ last mission —ill herself and they say that the voyage might have cost her life— took her to the house of the duchess of Alba to comfort her while in labour.

We hope to awaken curiosity, to encourage further investigation, and maybe even challenge current obstetrical practices. [Wolfram Aichinger, Exhibition curator]

This Exhibition is part of the research project The Interpretation of Childbirth in Early Modern Spain (P 32263-G30), funded by FWF Austrian Science Fund. More information on this project is available on The Interpretation of Childbirth in Early Modern Spain and the online journal Avisos de Viena. Viennese Siglo de Oro Studies.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the following persons and institutions:

José Aragüés Aldaz (University of Zaragoza), Florian Bischof (Pfarre Großgmain, Salzburg), Blanca I. Bazaco (Archivo Regional de la Comunidad de Madrid), Javier Díez Llamazares (Archivo Regional de la Comunidad de Madrid), Costanza Gislon Dopfel (Saint Mary’s College of California), David Fliri (Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Vienna), Isabel García Ramírez (Archivo Histórico Diocesano de Madrid), Raquel González Rodelgo (Archivo Regional de la Comunidad de Madrid), Ernst-Heinrich Harrach, Mauricio Herrero Jiménez (University of Valladolid), Ilse Jung (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), Marie-France Morel (Société de l’Histoire de la Naissance, France), Museo del Prado (Madrid), Pushkin Museum (Moscow), José Navarro Talegón (Fundación González Allende), Laura Oliván (University of Granada), Gudrun Swoboda (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), Adrian Wilson (University of Leeds), Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Munich), Biblioteca Nacional de España – Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Bibliothèque Nationale de France – Département des Manuscrits (Paris), British Museum (London), Kirche Hindelbank (Bern, Switzerland), Convento de las Descalzas Reales (Madrid), Fondazione Accademia Carrara (Italia), Geroztik Historia Museo Birtuala (País Vasco, España), Sonsoles Martínez, Musée des Augustines – Musée de Beaux-Arts de Toulouse (France), Musée des Beaux Arts de Rennes (France), Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (Rotterdam, Netherlands), Saint George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, Windsor (United Kingdom), Staatsgalerie Stuttgart (Germany) and Pia Walnig (Allgemeines Verwaltungsarchiv, Vienna)

Special thanks go to the Austrian Science Fund and to all those who have collaborated on the research project The Interpretation of Childbirth in Early Modern Spain (P 32263-G30).

Chief Editor: Wolfram Aichinger, University of Vienna.

With the contribution from:

Wolfram Aichinger (University of Vienna), Clara Bonet (Catholic University of Valencia), Alice Dulmovits (University of Vienna), José Antonio Fernández Fernández (University Rey Carlos, Madrid), Hannah Fischer-Monzón (University of Vienna), Alessandra Foscati (KU Leuven), Karin Fuchs (University of Vienna), Sabrina Grohsebner (IFK, Internationales Forschungszentrum Kulturwissenschaften, Vienna, University of Vienna), Tamara Hanus (University of Vienna), Lisa Heilig (University of Vienna), Jone Nere Intxaustegi (University of Deusto, Basque Country, Spain), Nina Kremmel (Liechtensteinisches Gymnasium, Vaduz, University of Vienna), Kurt Kriz (University of Vienna), Rocío Martínez (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid), Hannah Mühlparzer (University of Vienna), Pilar Panero (Universidad de Valladolid, Spain), Fernando Sanz-Lázaro (University of Vienna), Christian Standhartinger (Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften), Marie Stockinger (University of Vienna) & Jesús M. Usunáriz (University of Navarra, Spain).

Editorial Board: Wolfram Aichinger, Tamara Hanus, Lisa Heilig, Rocío Martínez, Hannah Mühlparzer, Fernando Sanz-Lázaro, Marie Stockinger.

Editing of translations into English: Sally Alexander and Rocío Martínez.

Editing of the texts in Spanish: Fernando Sanz-Lázaro.

Recommended reading

Arjona Castro, A., El libro de la generación del feto, el tratamiento de las mujeres embarazadas y de los recién nacidos. Tratado de Obstetricia y Pediatría del Siglo X, de Arib Ibn Sa’id, Sociedad de Pediatría de Andalucía Occidental y Extremadura, 1991.

Bettini, M., Nascere. Storie di donne, donnole, madri ed eroi, Einaudi, 2018.

de Carlos Varona, María Cruz, Nacer en Palacio. El ritual del nacimiento en la corte de los Austrias. Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, 2018.

Bernis, C., Varea C, Hour of birth and birth assistance: from a primate to a medicalized pattern?, American Journal of Human Biology, 24 (1), 2012, pp: 14-21.

De Carlos Varona, M.C., Nacer en palacio. El ritual del nacimiento en la corte de los Austrias, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, 2018.

Dopfel, C., A. Foscati, A. Parmeggiani, Nascere: Iconografia, Medicina, Agiografia dal Tardoantico al Rinascimento, Il Mulino, 2017.

Filippini, N.M., Generare, partorire, nascere. Una storia dall’antichità alla provetta, viella, 2017.

García Herrero, M.C., Administrar del parto y recibir la criatura‘: Aportación al estudio de Obstetricia bajomedieval“, Aragón en la Edad Media, 8, 1989, pp. 283-292.

García Santo-Tomás, E., Signos vitales. Procreación e imagen en la narrativa áurea, Iberoamericana, Vervuert, 2021

Gélis, J., L’arbre et le fruit: La naissance dans l’Occident moderne (XVIe-XIXe siècle), Fayard, 1984.

Hearn, Ka., Portraying Pregnancy: from Holbein to Social Media, Chicago University Press, 2020.

Hopwood, N., Fleming, R., Kassell L., Reproduction. Antiquity to the Present Day, Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Hrdy, S.B., Mothers and Others. The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding, Harvard University Press, 2011.

Labouvie, E, Andere Umstände. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Geburt, Böhlau, 2000.

Laget, M., Naissances : l'accouchement avant l'âge de la clinique. Le Seuil, 1982.

Loux, F., Le jeune enfant et son corps dans la médecine traditionnelle, Flammarion, 1978.

Morel, M.-F., La naissance au risque de la mort. D’hier à aujourd’hui, érès 2021.