September 2022

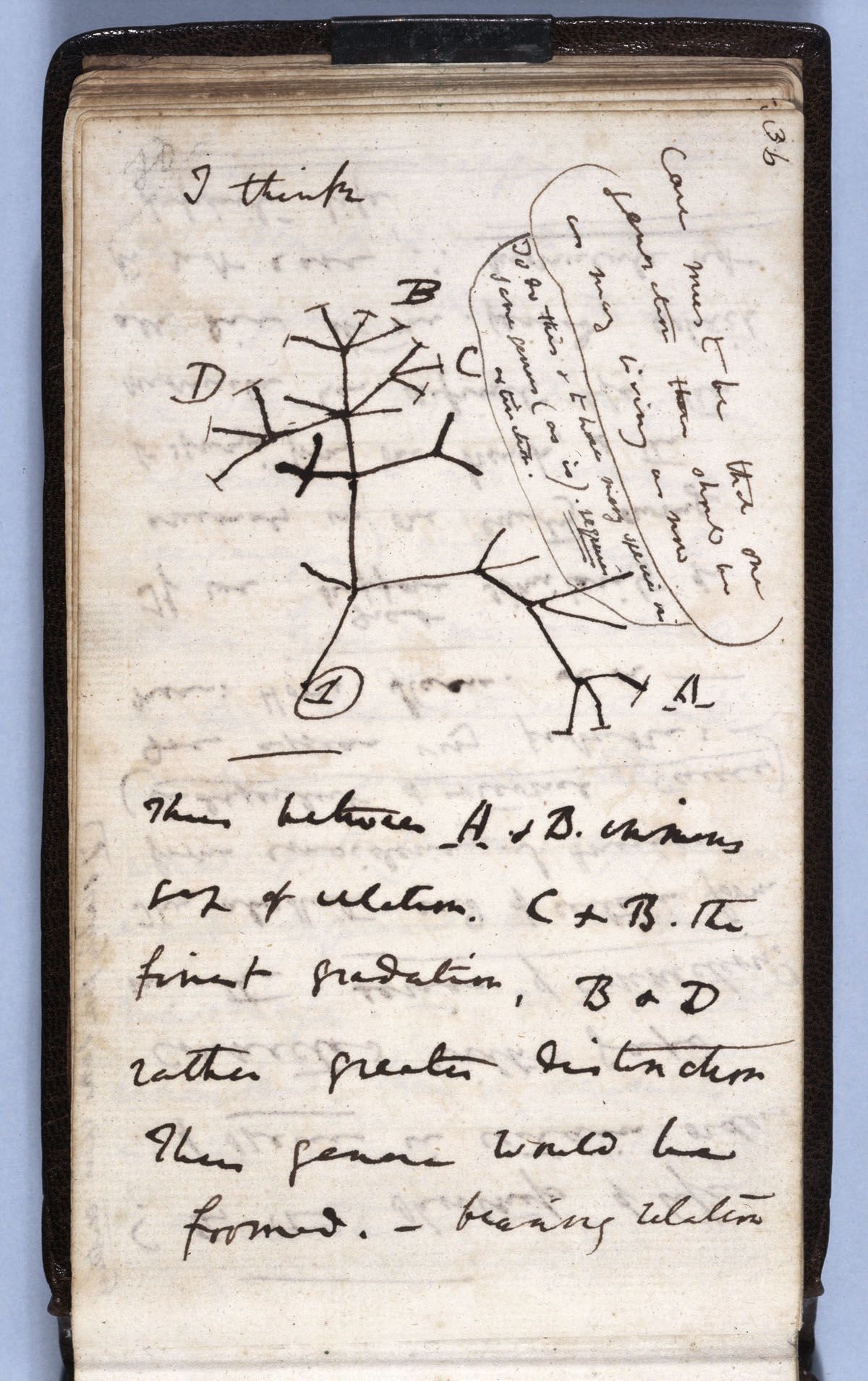

1837. «Tree of Life» sketch, Charles Darwin, notebook «B» © Cambridge University Library

1837. «Tree of Life» sketch, Charles Darwin, notebook «B» © Cambridge University Library

Darwin’s notebook «B» and the «coral of life»

Cambridge University (UK) has custody of Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) legacy of documents. Early last April, the University made it known that two of his notebooks (the so-called «B» y «C»), which had gone missing in 2001, had been returned anonymously to the library on 18th March with a note that said: «Librarian, Happy Easter X». The library authorities had for years thought that the notebooks had been mislaid somewhere in the institution among the 10 million books, manuscripts, maps, and other documents in its possession, after a request to photograph them in September 2000. Finally, after a thorough search in early 2020, the notebooks were declared stolen and on 24th November («Evolution Day», the anniversary of the publication in 1859 of On the Origin of Species by Darwin), the library made an international call for their recovery, which opened with a reference to the iconic sketch of the «Tree of Life» which illustrates the work and was drawn by Darwin in his notebook «B» in the summer of 1837.

During his voyage on the Beagle (December 1831 to October 1836), the young Darwin gathered his observations in a series of notebooks, which are on display in his home, Down House. Shortly before the end of the voyage, Darwin started to take notes in the so-called «Red notebook», basically about Geology and the formation of coral reefs, which he would finish on his return to England during the last months of 1836 and the first half of 1837. This notebook contains some of his first notes on the theory of evolution. He then bought several similar notebooks, small enough to fit in his pocket, so that he could take notes during his long walks through the countryside. They are devoted to specific topics and Darwin identified them with single, consecutive capital letters, «A», «B», «C», etc.

When he got back from his travels, the academic world to which he returned was still overwhelmingly anti-evolutionist, including Charles Lyell (1797-1875), who wrote the book which so greatly influenced Darwin during his voyage, Principles of Geology, and who would be an essential supporter of the young naturalist on his return to England and would be his intellectual interlocutor all his life. As Janet Browne points out in her biography, at the time Darwin felt very insecure about the evolutionary ideas which had arisen during his voyage on the Beagle, but his intellectual independence and bravery were the key to their development, a long and considered process.

In July 1837 Darwin begins his notes in the now recovered notebook «B», the first on the «Transmutation» of the species, to be followed by three more on the same theme, the series having been completed in 1839. On page 36 (the pages were numbered by Darwin himself) is the evolutionary sketch shown in this piece. Above it we read «I think». And top right there is text circled twice:

«Case must be that one generation then should be as many living as now. To do this & to have many species in same genus (as is) requires extinction.» (The word «requires» is underlined twice.)

Beneath the sketch there is more text which spills over onto page 37:

«Thus between A & B immense gap of relation. C & B the finest gradation, B & D rather greater distinction. Thus genera would be formed bearing relation to ancient types with. —several extinct forms.»

Darwin then explains that starting with a common ancestor (marked «1» in the sketch) 13 species persist in the present, represented by the lines which end with another perpendicular line, and another 12 species are extinct, corresponding to those lines with no end, short perpendicular line. The groupings of line at their base show their taxonomic link, which is now also phylogenetic.

Darwin was 28 years old when he sketched this diagram. By then his intuition is telling him that the evolutionary process is determined by random biological changes which occur between successive generations of a species, and he quickly associates this with the variability which derives from sexual reproduction (in those days nothing was known about the hereditary mechanism). But he does not know what the mechanism is which orientates that random generation of biological variability towards the diversification of lineages and the appearance and extinction of new species, as his sketch illustrates. As he explains in his autobiography, he would find it while reading «for amusement», a work by Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) called An essay on the principle of population (1798), which gave him the idea of natural selection, that is, the preservation of the variations which are favourable to survival and the destruction of those which are unfavourable, among those created by an excess of descendants («the struggle for existence»), which leads to the forming of new species in a constantly changing environment. He notes this down on the 28th September 1838 on pages 134 and 135 of notebook «D»: «I had at last got a theory by which to work».

In June 1842 Darwin believes himself ready to write a «brief abstract of my theory in pencil in 35 pages», which he lengthened out into a 230 page manuscript in the summer of 1844. 15 years were yet to pass before the publication of his On the origin of species, whose only illustration (pages 116-17 of the first edition) consists of two evolutionary diagrams which quite clearly derive from that sketched in notebook «B».

But let us focus on the sketch from 1837 again. The lineages diversify in a circular plan, not a directional one. Previously, on page 26 of the same notebook, Darwin had written: «The tree of life should perhaps be called the coral of life, base of branches dead». And in fact, life splays out like a coral rather than like a tree with a straight trunk. Here, freshly sketched, is the essential radicalism of Darwin’s ideas, the antithesis of Lamarckian idealism: evolution is not linear, has no direction and means a gradual perfectioning of the species, which transform into superior ones, a theological consideration which inevitably leads to the idea that our species is the culmination of Evolution —no longer of Creation. «It is absurd to talk of one animal being higher than another», writes Darwin on page 74 of notebook «B».

Buried in Westminster with a State funeral, his essential legacy was buried with him. His funeral gave way to the long period known as «the decline of Darwinism»: Darwin managed to get evolutionism fully accepted during his lifetime, but after his death it was tainted by a finalist and anthropocentric ideology which was just the contrary to his ideas. Many decades were to pass before the ideas sketched by Darwin in his diagram in 1837 were fully integrated into our current understanding of evolutionism and the diversification of life, powerful but random, and of our humble origins as primates and our insertion, as just another species, in Nature.

Carlos Varea is member of the Biology Department at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain), president of the Association for the Study of Human Ecology and co-director of the Virtual Museum of Human Ecology.