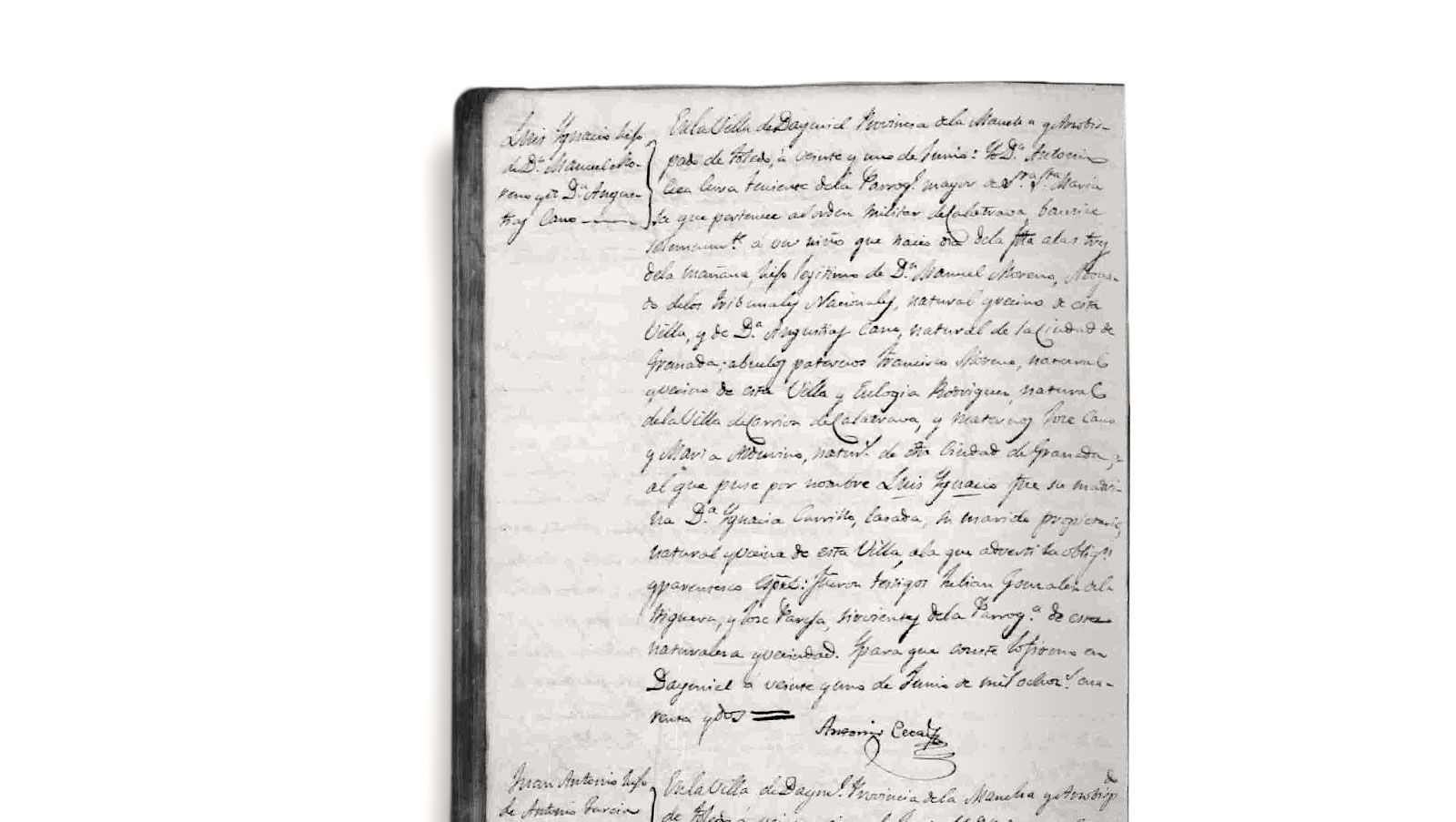

Daimiel (Province of Ciudad Real), One of the First Records of the Hour of Birth.

I. Cycles of Life and Death in a Mountain Village

Human childbirth is the process which best illustrates our species’ biocultural identity. Since reproduction is a biological imperative, there is one common goal seen across the entirety of humanity’s diverse groups and populations: the survival of both mother and child. This is why the ancestral tendency still endures for mothers to go into labour at night.

From our initial condition of nocturnal insectivores, fifty million years ago we primates evolved into daytime fruit-eaters, and this in turn led to the growth of the brain and the development of the complex social interactions which characterise us. This diurnal routine was the critical factor that led to primates generally giving birth at night: it allowed the mother to have her offspring, clean and groom it, and begin feeding it without fear of predators or the need for displacement.

For the last one and a half million years, as our ancestors fanned out over the savannah, maintaining this pattern of giving birth during the night remained critical. Bipedalism brought with it the narrowing of the birth canal which, together with the increased size of the braincase, made the human birthing process increasingly prolonged and prone to complications. We emphasise this evolutionary feature so strongly here in order to highlight just how pivotal it is to the specific characteristics and cycles of human childbirth that safeguard the wellbeing of mother and baby.

We don’t have an abundance of data on times of birth prior to the advent of medical specialisation, but all the same the available institutional records in western societies in the 19th century (such as the Casa de Maternidad in Madrid) show a clear trend towards the nighttime, at least in those cases where labour was of short duration and devoid of complications. The register of the 2,754 births in the Spanish municipality of Daimiel (Ciudad Real) between 1839 and 1850 confirms this. In the parish baptismal records, among these the one pictured here, the hour of birth was given as being between one and twelve, of either “the morning” or “the night” as was the custom in Spain at the time, and determined using some sort of sundial. The records in this sample show a clear predominance of births concluding either at night or in the early hours of morning.

Circadian rhythms are regulated by daylight through the secretion of melatonin. The majority of the physiological mechanisms involved in childbirth, including uterine contractions, intensify at night. As a result, we can see the circadian pattern more clearly if we compare the hour of birth in the days around the summer and winter solstices: in winter, with its longer nights, the time of childbirth is concentrated around the late night and early morning, while in summer with its shorter nights the time of birth starts later and goes on until mid-morning.

Contemporary data analysed from the Hospital La Paz in Madrid also reveals a circadian pattern in the time of rupture of the amniotic sac, which is even clearer than in the hour of birth. This makes sense: the duration of labour depends on factors such as whether there is more than one baby, and possible complications. First-time mothers have longer and more complicated deliveries as a rule, and a dilation rate three times slower. [Carlos Varea and Lara Carasa.]