A Saint’s Protection and Emergency Baptism

III. Evidence of Early Care

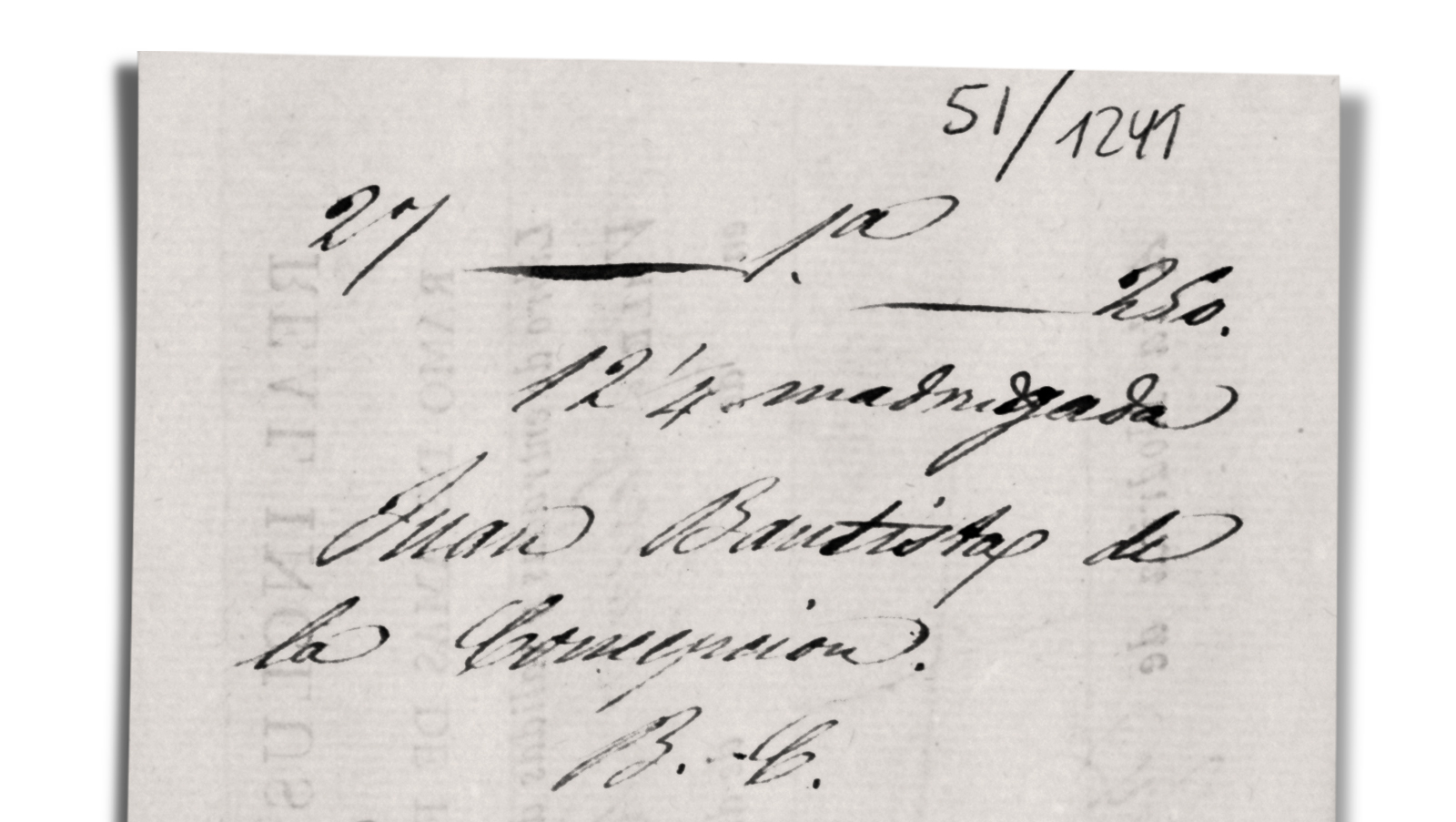

On a newborn’s arrival at the Madrid Inclusa, a serial number was assigned to it and recorded in the institution’s files. Juan Bautista’s was 27-1.a-250. This number was then inscribed on a collar placed around the foundling’s neck. Juan arrived at night, as did the great majority of foundlings. In his case this was just after midnight on a cold winter’s night, its temperature below 5oC, and well-lit by what would be a supermoon the following night.

Had this baby, reported in a different record as “appearing to be just born» (see section 13), come into the world that very night? We have a clue lying in his given name of Juan Bautista de la Concepción, suggesting that he may in fact have been alive for just a little longer. The saint of this name (or beatified person to be exact) was held to be the founder, in Córdoba, of a reformed branch of the Trinitarian Order – and his feast day was February 14, as can be seen in the calendars and diaries of the time. It was common for foundlings to be commended to the saint of the feast day of their birth, and baptised with the same name. Indeed, this was a common practice not only for foundlings but for all children at the time. We can reasonably infer, then, that Juan had been born on February 14 1859, the day before his exposure.

Why, then, would a day have passed before he was deposited in the Madrid Inclusa? There are various possible explanations. Could he have been born outside Madrid, and then taken there the next day? This is unlikely because there is no note in his record of the four ducats’ payment which was customarily included along with an abandoned child from outside the city. Perhaps the mother had died in labour, or of associated complications, and only then had the decision to expose him been made. It may also have been that he was thought too weak, immediately after his birth, to be taken outside and exposed on a cold February night…

There’s one more clue, in the letters “B.C.” added at the bottom of the entry shown here. These stand for “Bajo Condición”, or sub conditione, and their use signified that a child had already received emergency baptism, subject to verification that this had been performed correctly. We must picture, then, a baby born very frail, perhaps prematurely, and one among those present in the delivery chamber pouring the salvation water upon him and making the formulaic utterances. It was generally believed that if this was not done with sufficient expedience, and a child died, its soul was thereby condemned to the shadowy spaces of limbus puerorum and would never attain to glory.

It is easy for a contemporary reader not to fully appreciate quite how all-consuming, socially and culturally, this obsession was of not letting a baby die unbaptised. Yet in those times grieving parents would sometimes journey to holy places and beg for their child to be brought back to life, albeit only for long enough for holy baptism to be performed. Preachers denounced slave-owners who forced their pregnant enslaved women to perform onerous tasks, on account of the consequent risk of their miscarrying. A man of the Church would come out in favour of performing caesarean sections post mortem, in order that an unborn child receive baptism. Authors of obstetric texts agitated for appropriate training to be given to midwives. Churchmen would relate miracles which had enabled the dreaded outcome to be avoided, as did dramatists and writers of comedies. In summary, the entire populace was gripped by a terror of limbo and clamoured for expeditious baptisms, within only a few days of birth – or even straightaway, when circumstances called for it.

And finally we have the author who wrote in defence of the 19th century Casas Cuna on the grounds that, while these institutions did certainly abet “sinful behaviour”, and many babies deposited there were already on the verge of death, meaning that nothing of any practical use could be done for them, these institutions performed the vital services of protecting the mothers’ good names and, above all, reducing the risk of infanticide (of unbaptised children, that is).

Who was the right person to administer the salvation water in critically urgent cases? Beyond a doubt this would have been the midwife, as the person best qualified to make an accurate assessment of a newborn’s vital signs. We can imagine, then, Juan being born in a private household and the midwife taking him to the Inclusa after performing emergency baptism, along with some sort of note to this effect. (The subsequent, solemn baptism would later provide exorcism and the holy oils.) It’s certainly a plausible enough reconstruction, given the evidence – and the midwife envisaged in it would definitely not have been the first to play such a part in a foundling’s fate.

Most foundlings were abandoned only a few days after being born. Where the birth had taken place in secrecy, this made sense: the baby needed to “disappear” before it was noticed by vigilant relatives or neighbours. There may have been an additional purpose, however, in carrying this out so expeditiously: to avoid creating an unshakable attachment between mother and suckling. Once breastfeeding is initiated, the body releases potent bonding hormones that make the prospect of abandonment emotionally devastating for the mother, however compelling the practical reasons might be. These mothers forsook their children, then, or were separated from them, before lactation could make them reject this course of action. [Wolfram Aichinger and Lisa Heilig.]