What the “Letters” Can Tell Us

III. Evidence of Early Care

To learn as much as possible of these foundlings’ fates we combed the archives of the Madrid Inclusa and other Casas Cuna, asking questions such as how, where and when were these abandoned children born? Who attended the mother during labour? Why did she have to give up her child?

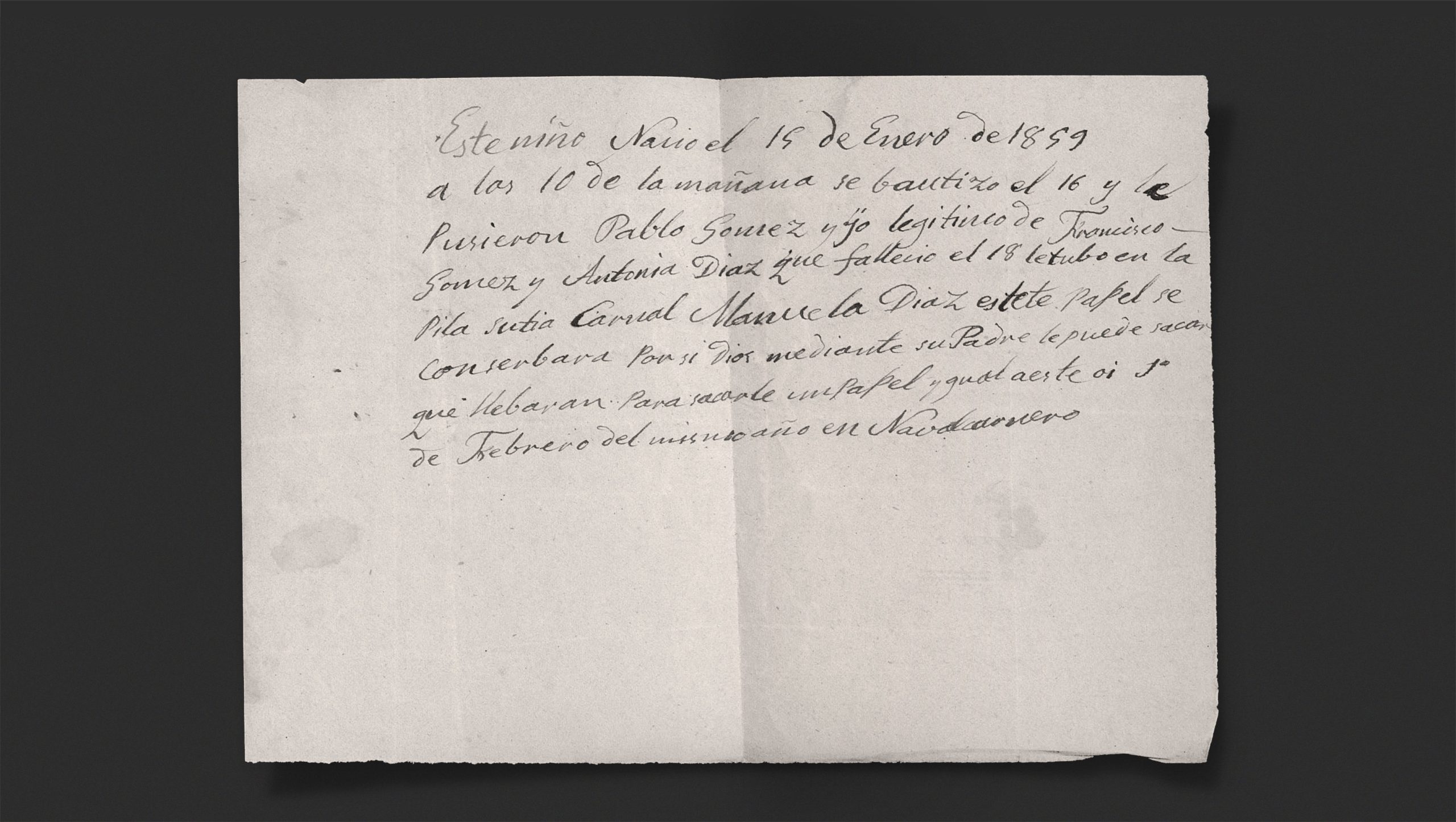

Most of the time these questions were left unanswered and the best we could do would be to analyse clues, for example what could we tell from an infant’s clothing, from a religious object affixed to it, or from its state of health. But this was not always the case, and occasionally a depositor would leave a letter or note together with a child, giving us some additional details of its origin story. We have here an example from almost the same time as when Juan Bautista was born. The document shown speaks of baby Pablo’s difficult start in life. He was born on 15 February and baptised the next day, with his mother’s sister as godmother. But then three days after giving birth to him his mother died, and on 1 March Pablo was handed over into the care of the Madrid Inclusa with the promise that his father would soon come for him, bearing a copy of the same letter. We wonder whether perhaps the father was unable to defray the costs of a wet-nurse, or if there was no female relative or neighbour available to give the infant its first nourishment. What we do know is that Pablo was later to die, in Hontoba, Guadalajara, on 23 August that same year, in the charge of the wet-nurse Juana Sainz.

Why do documents like this matter? Above all, they serve to give the lie to the stock explanation of the entire foundling ecosystem that was current at the time: a mother, deceived and betrayed by an irresponsible lover, overcome by poverty and terrified of the wrath of father and brothers, and of village gossip. A woman in this predicament would need to keep her maternity a secret and would therefore abandon her baby in a Casa Cuna turntable. Or perhaps she would have sought the protection of the Casa de Maternidad associated with the Inclusa, where women were permitted to enter some weeks before their time – presumably to conceal their “interesting position”, as the press of the day euphemistically termed it – and then have their child anonymously.

And many stories like this can indeed be seen in the archives. While in the villages an illegitimate child was an exception, in Madrid this was no longer true. In his demographic study of the Madrid of 1849, Pedro Monlau found 6,583 legitimate births, as against 1,853 children born outside wedlock.

But this standard narrative of the unmarried mother, etc., is just one of a wide range of actual storylines that led up to a child being handed over to a Casa Cuna. The records tell us of mothers unable to care for their child because they were laid up in hospital, or who weren’t able to suckle, or who couldn’t manage because the father had died during the pregnancy, thus leaving the child unprovided for. Some weren’t able to take on the unexpected burden of twins, and still others promised to come for their baby once the father had returned from the New World. (This last case was more common in the Casa Cuna in Cádiz than in Madrid, naturally enough.)

There are very few cases which mention sisters, aunts or grandmothers. Where the female family support network was in place, we infer, a child would almost never be abandoned, however precarious the financial circumstances. A letter like the one shown here, therefore, which does allude to an aunt by blood, is a complete outlier. [Wolfram Aichinger.]