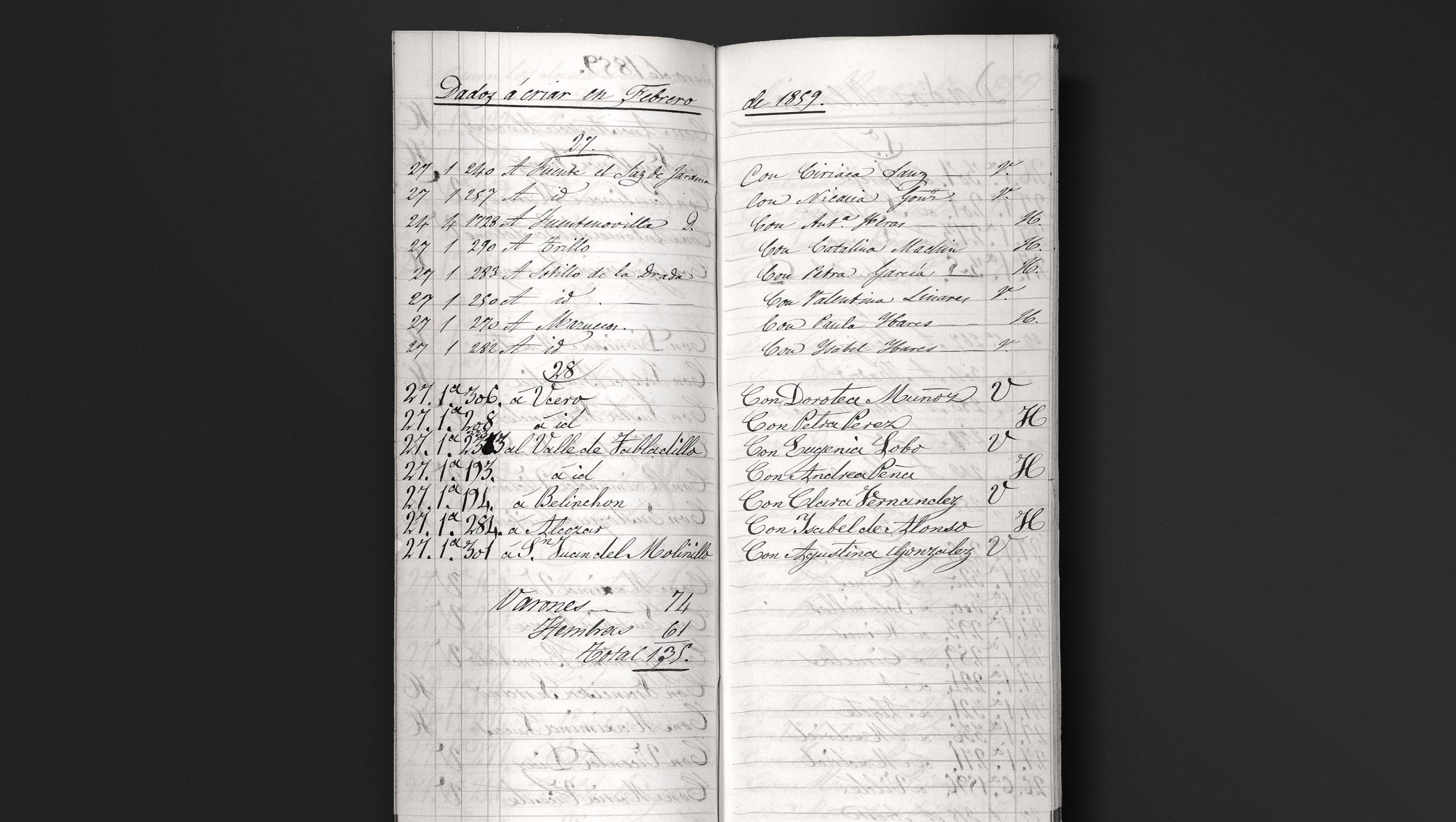

“Put out to Nurse” in February 1859.

II. From the Inclusa to Sotillo de la Adrada

On 27 February 1859, eight babies were “put out to nurse” into the care of a village wet-nurse from one of the provinces surrounding Madrid. Two went to Fuente el Saz de Jarama (Madrid), one to Fuentenovilla (Guadalajara), one to Trillo (Guadalajara), two to Sotillo de la Adrada (Ávila), and two to Mazuecos (Guadalajara). On the 28th there were seven: two were sent to Ucero (Soria), two to Valle de Tabladillo (Segovia), and one each to Belinchón (Cuenca), Alcozar (Soria), and San Juan del Molinillo (Ávila).

At the bottom of the page in the illustration here, we can see the total number of infants sent out to the villages in February: 74 boys and 61 girls, 135 in sum, an average of 4.8 per day. Over the course of 1859, of the 1,406 transferred around Castile by the Inclusa some 1,229 died, a mortality rate of 87.4%.

The Valle del Tiétar made its debut as an Inclusa destination in about 1850. But once this activity of taking babies in to nurse from elsewhere got started, the numbers both of wet-nurses and foundlings skyrocketed. In 1859 three children were taken to Sotillo de la Adrada, with one of them dying. In 1863 the respective tallies were fourteen and fifteen. In Pedro Bernardo, the largest municipality in the area, the growth was even more spectacular. The number of arrivals rose from none in 1854 to seventeen in 1855 and peaked at 87 the following year. It then declined, but still stayed high: 75 in 1857, 49 in 1858 and 36 in 1859. In his records of infant deaths in 1858, the parish priest even established a separate category for the Inclusa children: 57 of them died that year, while there were 67 deaths among those born locally.

Until the start of that decade, neither village had ever taken in Inclusa foundlings. What happened to turn this on its head? Various factors would have been at play in these times of economic boom and the revolution in working practices, communications and lifestyles: chief among these would have been an increasing demand for wet-nurses as the capital grew, with its fine houses and the unwanted babies of their staff of maids, serving-women, watercarriers, washerwomen, purveyors of fresh produce, seamstresses and factory workers. The arrival of the railway, together with widespread road improvements, shortened the journey between the city, 91 km in the case of Sotillo de Adrada, and the mountain villages. The Inclusa may also have been on the lookout for locations where the babies “put out to nurse” had a better chance of surviving – villages with milder summers and a generally healthier environment. Some destinations became known for “having better milk”, while others got a name for being relatively perilous for their foundlings. For a more thorough analysis we would need to look in detail at how this modernisation process played out village by village, each with its own peculiar balance of manufacturing, artisanship, agriculture, economic conditions and water or air pollution from local industry – as well as the division of labour between the sexes. Pedro Bernardo, for example, close to Sotillo in the Valle del Tiétar, had traditionally been an important centre for textile production, and still remained one in the 19th century.

This taking in to nurse of foundlings from the city appears all of a sudden to have “gone viral”, as it were. While the overall system was a good fit with the general circumstances in the villages of the time, or at least with those of certain groups among the people there, it could only really arrive definitively once all the requisite conditions were met, and then someone took the first step and kicked it all off. Among other things, before the first incluseros came and were nursed for reward, it was already relatively common for a woman to feed another’s child at her breast: a cousin’s, a sister’s, a friend’s – someone who for whatever reason couldn’t feed the baby herself. Such a favour would not generally be paid for in money, but would certainly be taken well into account in the mutual support networks that were so vital in these small communities.

It’s worth noting that, in many cases, more than one foundling would leave for the same destination. On 27 February 1859, then, to take the example given above, two children left for Sotillo de la Adrada, two for Fuente el Saz, two for Mazuecos (these last two taken in by two women sharing a surname, Paula Ibares and Isabel Ibares). The wet-nurses would not always make the weary journey to Madrid alone, then, but often travel in twos, threes or small groups, together with a friend, a cousin or a sister. [Wolfram Aichinger.]