Nursing Care Costing 50 Reales

II. From the Inclusa to Sotillo de la Adrada

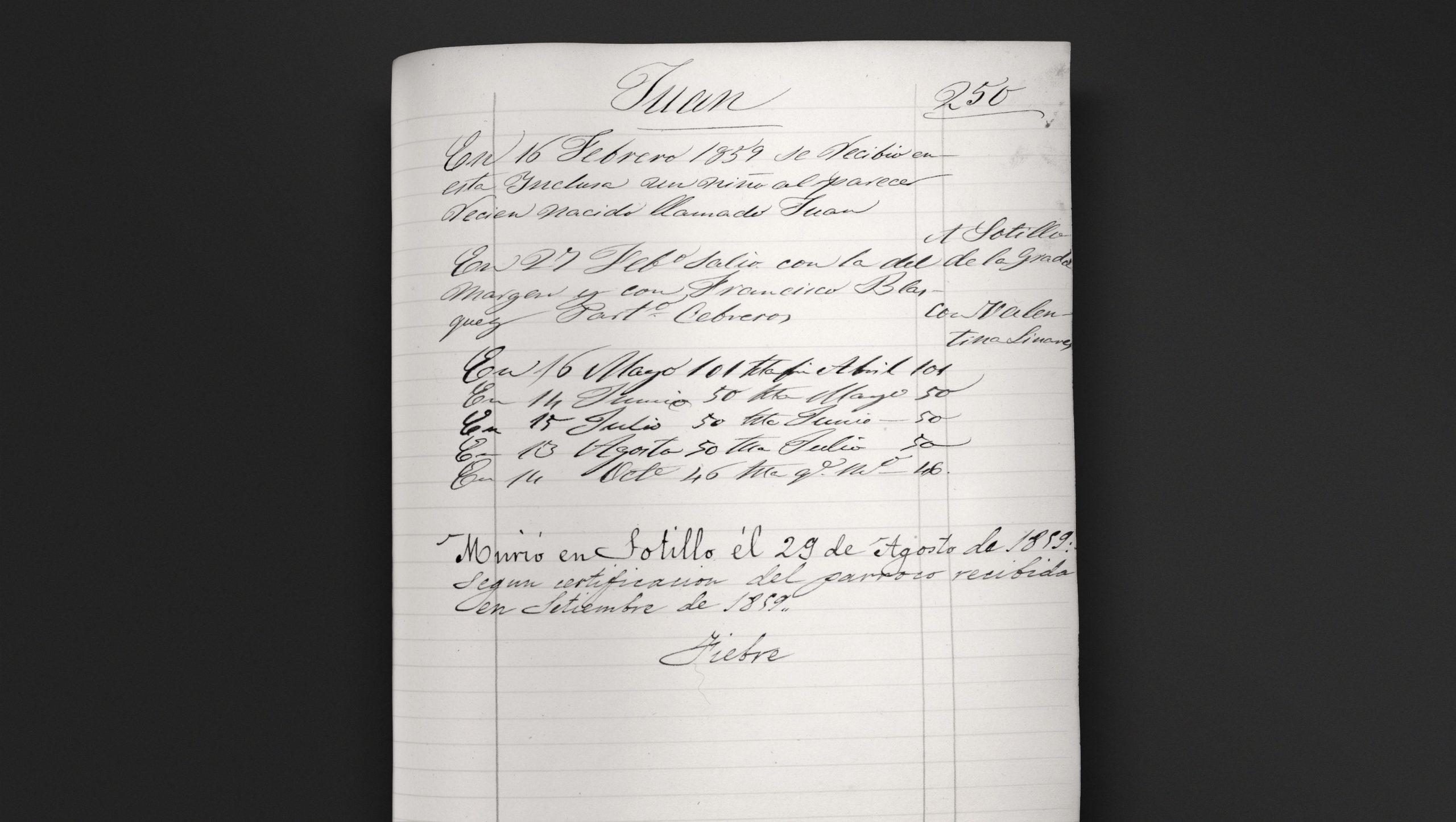

While there were plenty of day-workers’ wives among those applying to take in a foundling, the majority were village women married to small tenant farmers. These were poor peasant folk, certainly, but not right at the bottom of the social hierarchy, and for these people any extra money coming in would be put to good use helping them just keep going. The 50 reales paid for Juan Bautista’s care when they took him in would have made a difference in the domestic economy of Paula Martín, her husband Pascual Guerra and their five living children.

Did the rural wet-nurses faithfully discharge their duties? Were the Inclusa children well looked after? Cases varied wildly, and there are reports of neglect and cruelty just as there are others of kindness and nurturing bestowed on a baby joining a village family household. Where the foundling took the place of a dead child, as opposed to adding in number to and competing with its “milk-siblings”, greater effort would probably have gone into assuring its wellbeing than if it had found itself in a home with too many mouths to feed and not enough to go round. The Society of Ladies endeavoured to implement controls, and sent out inspectors engaged by the institution. Some priests and mayors submitted reports declaring whether a child was healthy, if it still wore the collar fitted upon it in the Inclusa, and if it was well fed. In any event, the risk of death was severe back then for any child in very early life, and heat, bad water, diarrhoea and summer fevers decimated all infants, locals and strangers alike.

The tally of dead incluseros was frankly horrific, but then infant mortality in general was just as shocking. We can forget that this is the feature that most starkly distinguishes modern western life from the not-so-distant past. The Spain of the 19th century was a joyous world, replete with little children; yet at the same time it terrified, since one in every two babies born would not complete its first years of life. (This is illustrated by a detail from the book Madrid en la Mano, published in 1850 by Pedro Felipe Monlau y Roca, page 68: in the Madrid of 1849 there lived 41,000 children under six, but only 9,583 adults aged between 60 and 80.)

On balance, nevertheless, the chances of survival for an Inclusa child were better in one of the villages than if it had stayed in Madrid, inside the Home. [Wolfram Aichinger and Lisa Heilig.]