Love Affairs in May, Babies in Winter

I. Cycles of Life and Death in a Mountain Village

“Bereaved on Palm Sunday, delivered of a child every Twelfth Night, is my good friend’s maid”

(He made love to his maid, then separated from her each Palm Sunday, and after Easter he returned to her and got her with child, and she would bear it on Twelfth Night)

Gonzalo Correas (1571-1631), Collection of sayings and proverbs

“Easter is ending, fair maids,

Easter is ending!”

Luis de Góngora

Before mass migration towards the cities began, and lifestyles in Spain became more westernised, a relatively high proportion of children would be born in the late autumn or early spring – while summer was the season with the lowest number of births.

There is a wide variety of possible explanations for this: greater fertility in spring, family traits spanning various generations, holidays and paydays for servants and shepherds, prompting them to spend more freely and “let their hair down” in the company of the opposite sex… It has also been suggested that the annual agricultural cycle made it an imperative for women not to be bearing children just at the season when they were most needed for other tasks.

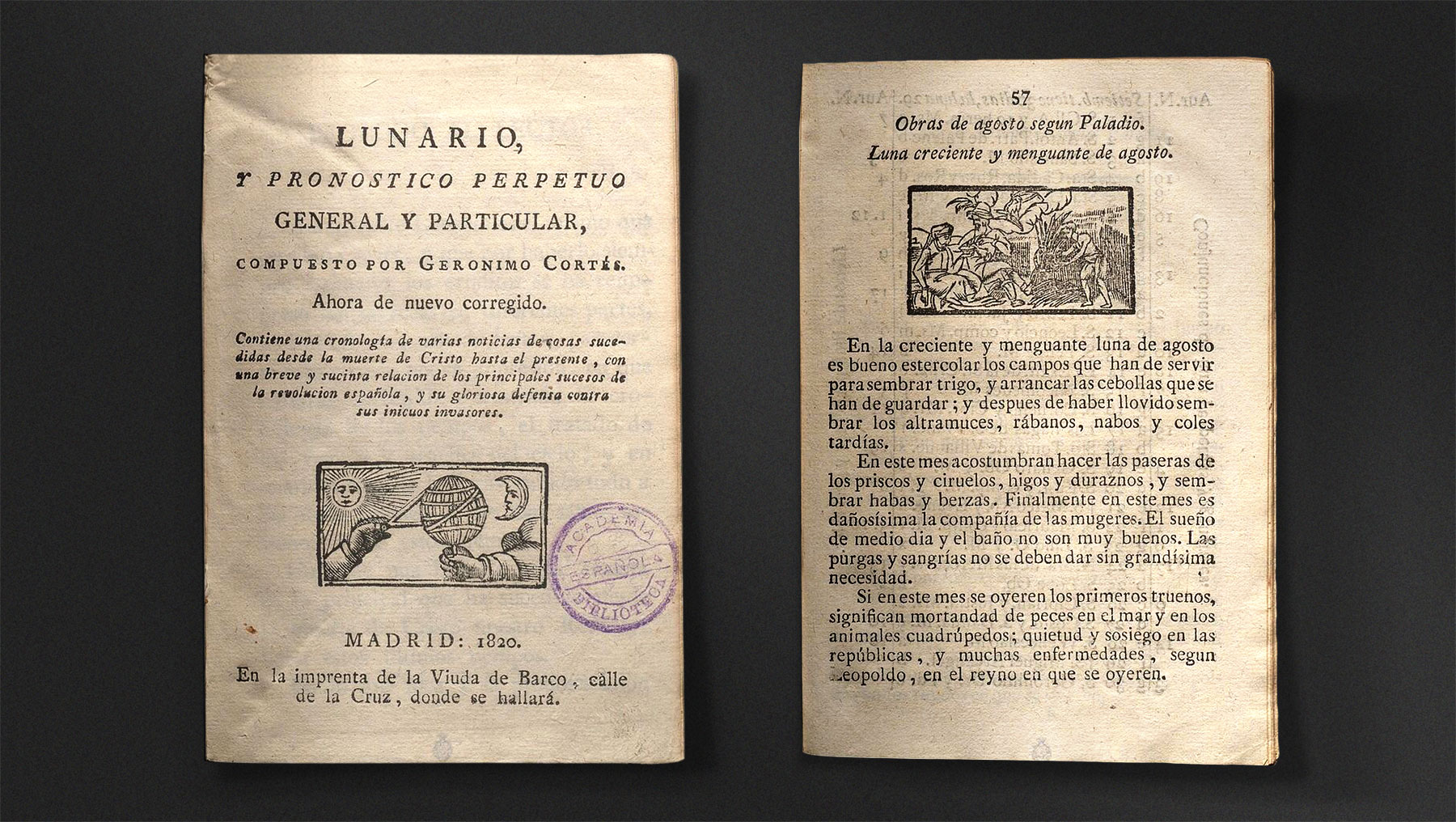

In his studies of childbirth in the early modern age, Ángel Torrents observes a clear drop in the rate of conception from July onwards, lasting from August until the end of the year. Those abstaining from sexual congress in high summer would have met with the approval of Gerónimo Cortés’s Lunar Calendar and Perpetual Forecast, General and Specific. Published in the late 16th century and remaining in print until the early 19th, it doesn’t mince words in its strictures concerning what activities to avoid in August: “during this month, female company is extremely detrimental”.

The religious calendar urges chastity during Advent, Lent, Sundays, Fridays and the main holy feast days. This annual cycle – probably pre-Christian in origin – divides the year up between, on the one hand, periods of dancing, rondels, merrymaking and general permissiveness, and others devoted to fasting, contemplation and charitable deeds. In his 14th century The Book of Good Loving, archpriest of Hita Juan Ruiz had his figures dance to the rhythm of Carnival, Lent and then the carousings in honour to the God of Love, which began after Easter. This was when the Archpriest himself would venture forth in search of amorous encounters. The high point of this season of love-making was the night of San Juan, midsummer night, when – as we read in Cervantes – a maiden would invoke the name of the lover picked out for her by the great saint, meanwhile keeping one foot in a tub of water.

It was certainly true that a high proportion of children were conceived in Carnival, and this explains the spike in births in October, November and December (no more precise period can be given, since the date of Carnival depends on when Easter falls, which in turn is determined by the capricious Moon, as too are the dates of all the feasts before and after Easter! The child born on 4 December 1856, for example – a late Carnival year – would very probably have been the work of “Don Carnal”; another born on the same day in 1818 – Ash Wednesday came very early that year – would have been conceived in mid-Lent).

Juan Bautista de la Concepción, the foundling from the Madrid Inclusa, was born on 14 February. His mother, whose name will never be known to us, would therefore have become pregnant in May 1858. [Wolfram Aichinger]