Foundlings’ Mothers, and Child Murderers.

IV. The Collective Imaginaries

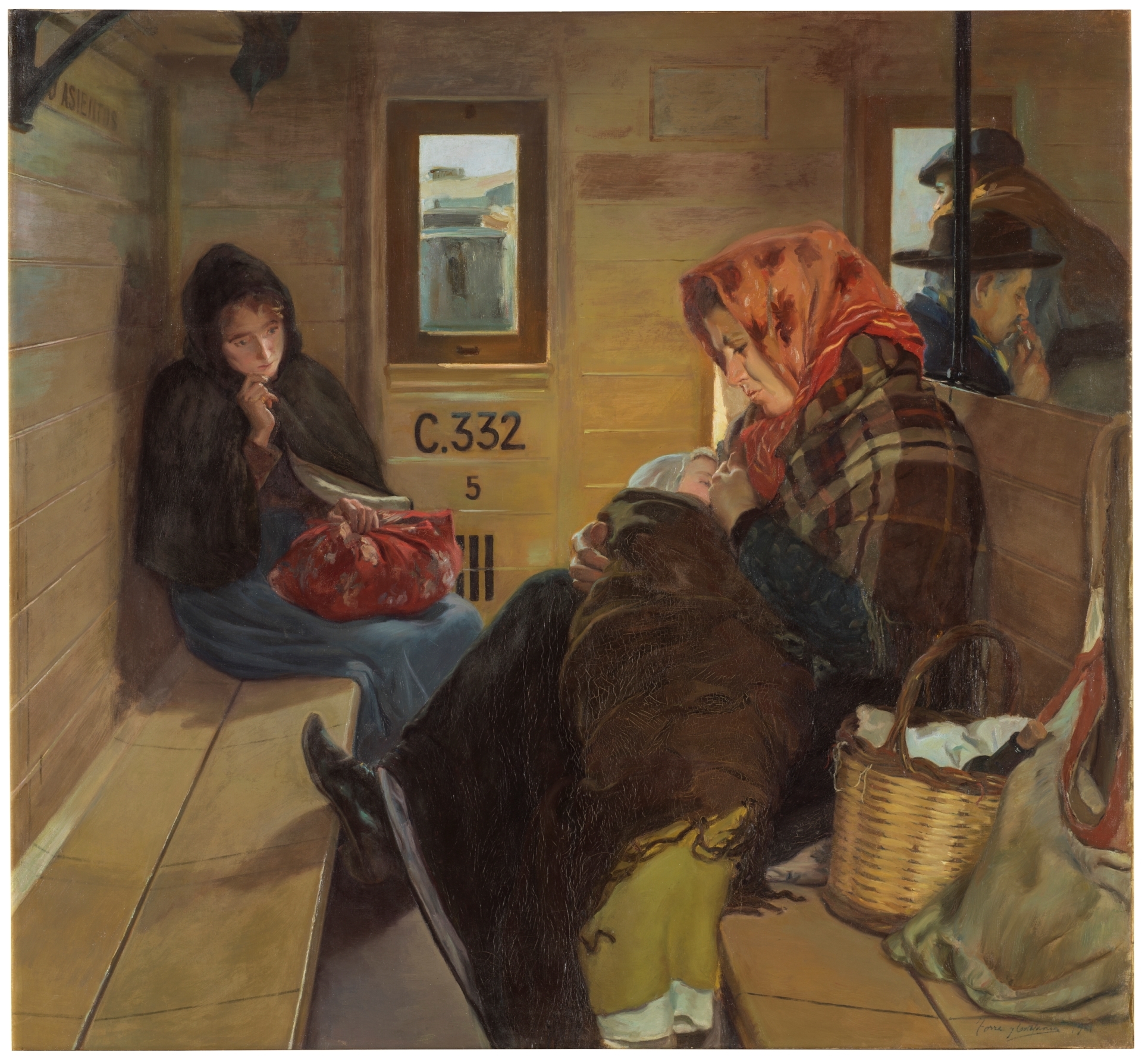

What circumstances could have brought a stout village woman bearing a suckling together with a shy, gaunt girl, in the same third-class carriage on a train bound perhaps for Ávila, Guadalajara, Segovia or Toledo? The one sits in serene comfort, with her lunch basket and bottle of wine, while the other is curled up in a corner, wishing she had never been born.

Let’s not be misled by the painting’s realism: this is an artistic composition. All the same, the events the picture hints at are absolutely of their time: the pinched young woman has perhaps just given birth, in secret, possibly at a midwife’s house, or in the Madrid Casa de Maternidad, where pregnant women from the villages went as well as those from the city. The village matron, by contrast, will be returning home with a foundling she has just collected, to nurse it there.

When “¡Inclusero!” was first publicly shown in 1901, it didn’t go unnoticed that the work openly mirrored an earlier painting by the Valencian master Joaquín Sorolla: in this analogous composition we are shown another young woman, in this case handcuffed and escorted by two civil guards, also in a third-class carriage. The title, “¡Otra Margarita!” (or Another Gretchen!, in reference to the infanticidal role of the same name in Goethe’s Faust), indicates the crime of which the woman is accused: the murder of her own newborn child. Sorolla had witnessed a scene similar to the one he later painted, likewise on a train, and had been deeply affected by it.

There is a great resemblance between the depictions of the mother of a foundling and the child murderer. And a comparison between the two paintings echoes a great controversy of the time, the raging debate between detractors and advocates of the Casas Cuna, and highlights the defining argument mentioned earlier in this study: that if it had not been for the Inclusa there would have been a glut of infanticides.

The Margarita child murderers went on to take their place in classical German literature. In France, Italy and Spain, by way of contrast, it was the Casas Cuna that penetrated the public imagination. We offer here the following contention, though well aware that more evidence is needed before this can be considered anything like conclusive. And that is that infanticide is a phenomenon related to Protestantism, whilst Catholicism favours the slower death of the Inclusa, one that comes after at least a short period of life, and could even be avoided altogether in a handful of happy cases. [Wolfram Aichinger.]