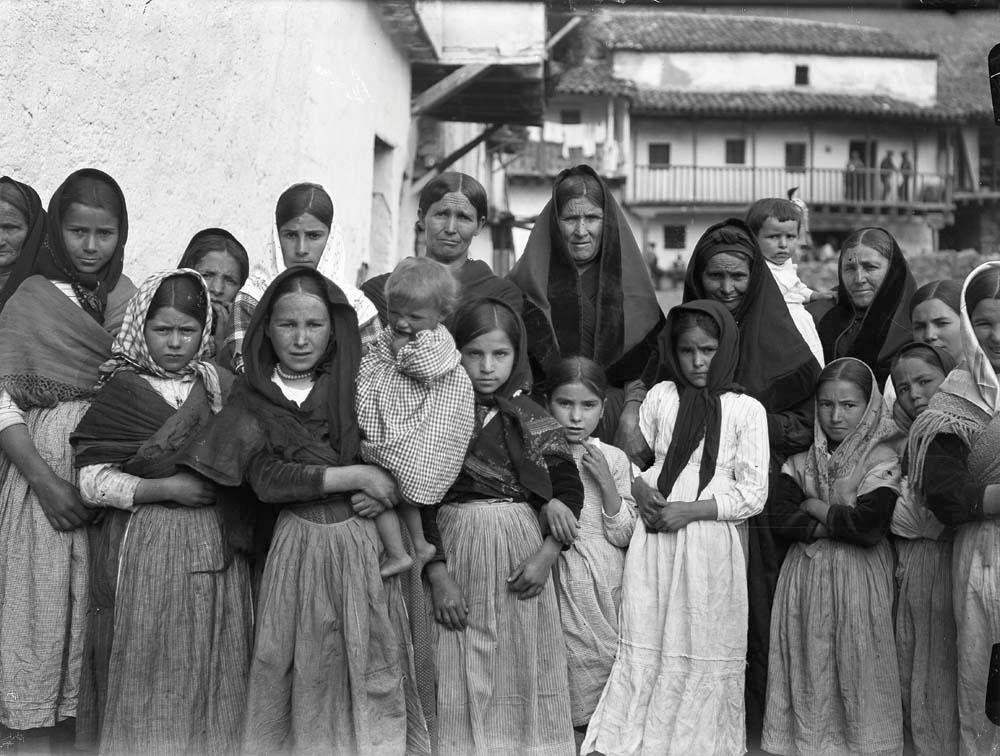

Cycles of Childbearing and Breastfeeding

I.Cycles of Life and Death in a Mountain Village

“The child who laughs not at seven weeks, either has no heart or heartless are its nurses”

Popular saying

“Blessed Santa Águeda,

Here I pray to thee,

That thou mayst heal my breast,

That the baby may suck”

Popular prayer

Paula Martín married in November 1842, at the age of eighteen. This was relatively early by the standards of the Valle del Tiétar, where a young woman of her time would generally marry at around 22. This may be related to the fact that her mother had already died by then. Paula became pregnant in July of 1843, and then had Venancio in April of the following year. Some sixteen months, then, separated wedding from birth. The remaining children were born in 1846, 1848, 1851, 1853, 1855 and 1857. Seven, in sum, over fourteen years of child-bearing.

And then later, in March 1859, this woman from Sotillo de la Adrada took in the foundling Juan, from the Madrid Inclusa. A year and a half, therefore, passed between the birth of her last child, Cipriana, and the commencement of her work as a wet-nurse.

Let’s take a closer look at the dates of birth of the couple’s children. If we look at the time elapsed between one confinement and the next, we can spot a certain regularity, and a pattern takes shape. Every birth was followed by a gap of more than a year; in three cases, the interval was longer than two years. And focussing on the period between when Eugenia (her third child) was born, and Bernabé Antonio (the fourth), we count two years and ten months. In no case, however, was there a pause of more than three years. The average intergenic period was of about 25 months.

There is a certain pattern, then, and this tells us that Paula – and many other common village women – did not, in fact, have children “with the regularity of the tree which gives fruit every year”, to use the words of the novelist Galdós. But then Galdós was speaking here of the reproductive frequency among only the middle-class women of this 19th century Madrid, a characteristic also seen in the royalty and aristocracy of the Siglo de Oro (Spain’s Golden Age), for example in Margarita of Austria (1584-1611): and it would be a bad mistake to extrapolate this tendency to the wider female population.

Why was this? Even taking into account other factors, such as pregnancies which did not go to term, thus going unrecorded, the root cause must have lain in lactation. Paula fed all her children from her own breast, and for more than a year, with the concomitant contraceptive effect of that, and also the very possible suspension of sexual congress. Breast-feeding reduced both fertility and – or so at least it was asserted by contemporary observers, and is also suggested by ethnographic studies – the inclination for masculine company.

Note that the taking in of the baby from the Inclusa matches this cycle perfectly. Paula’s seventh child, Cipriana, born in September 1857, would probably have been weaned in early 1859, and as a result she could then have offered her milk for reward, following a nursing period of fifteen to seventeen months.

This regular pattern of births and early care-giving in the village women was, we repeat, quite unlike what the historical record tells us of the fine ladies, duchesses and queens of the time. But of course, these mothers engaged wet-nurses, and that is what made possible the once-annual bearing of children remarked upon by Galdós. This breakneck pace would have been exhausting for the mother – and also one that deprived the child of its optimal source of nourishment.

We should recognise that, in a nation of nuns and spinsters, not all women attained to motherhood: by no means. Indeed, since the Lord laughs upon the plans of men, the overall trends could never have applied universally. In Fortunata and Jacinta, Galdós contrasted the astonishing fecundity of doña Isabel with Jacinta’s thwarted maternal longings, and also with the general dearth of children in the other families in his novelistic world. In the villages, as in the palaces, there were childless couples (despite however often so many of them resorted to herbs, wise women, pilgrimages, or vows to the Virgin and the saints). “Where the Lord gives you not children, the Devil gives nephews”, as the saying went: adopting the child of a sister or brother, or taking in a baby from the Inclusa, were socially acceptable strategies to safeguard the continuity of a family. This, however, was emphatically not the case with Paula Martín: she took in the Inclusa foundling to make some extra money and, very probably, to put an end to the debilitating cycle of gestation, confinement and nursing children of her own. [Wolfram Aichinger]