An Under-resourced Institution?

II. From the Inclusa to Sotillo de la Adrada

Barring the odd honourable exception, most histories of the Madrid Inclusa of calle Mesón de Paredes 74, and of other similar charitable foundations, tirelessly reiterate two stereotypes. The first is that the root cause underlying the mass abandonment of children was poverty, which is a most unhelpful, nebulous term. And the second, that the widespread ineffectualness of charitable institutions was the direct result of lack of resources.

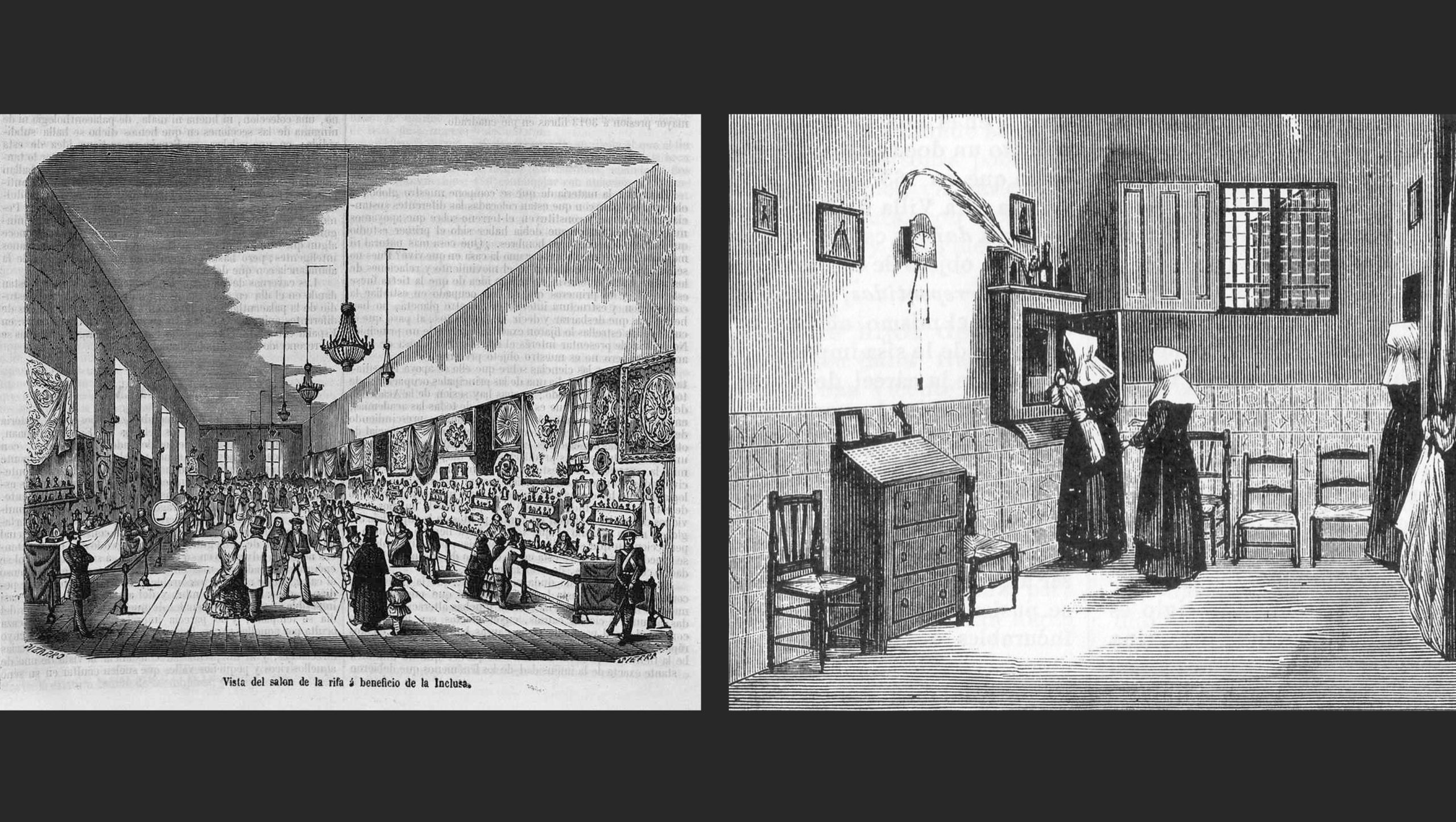

This second argument, shortage of cash, was already being put forward with respect to the Inclusa by Pedro Felipe Monlau y Roca in his book Madrid en la Mano of 1850. Yet in the same work he also spoke of the success of fund-raising efforts, such as one year’s Holy Week churchdoor charity collections, which had raised 171,227 reales! These were coordinated by the Society of Ladies of Honour and Merit, which oversaw the Inclusa in partnership with an economic foundation. A street market and raffle in aid of the Inclusa took place every February and was depicted in a magazine in 1857 (see left-hand image above).

The fact is that, despite their miserable lot, the Inclusa foundlings were very much in the public eye. The term Inclusa was adopted to refer to an entire district encompassing the Rastro, Peñón, Arganzuela, Huerta del Bayo, Encomienda, Cabestreros, Embajadores, Caravaca and Comadre neighbourhoods. And the Diario Oficial de Avisos de Madrid even published detailed monthly statistics tracking the number of Inclusa foundlings and the total donations received, together with the names of some of the benefactors, although others remained anonymous. It would even provide a list of non-monetary contributions such as syrups, hams, turkeys and cheeses.

Thanks to this journal we know what the total number of foundlings was at the end of February 1859, and how this number varied from the balance at the end of the month before. On February 1, then, the Inclusa had been guiding the fortunes of some 5,555 children put out into households, and of another 77 staying within its own doors. Over the course of the month there had been 175 new arrivals and 133 departures. Of the departures, 87 of these had been deaths in the external households and 34 inside the institution, with another five foundlings reassigned to the Colegio de Desamparados and four to the Colegio de Nuestra Señora de la Paz (these two institutions were for the education of children over the age of seven), and finally three children had been returned to their parents.

If writers such as Galdós are to be believed, in some cases one specific child from among those cared for in the Inclusa would receive preferential treatment, thanks to targeted cash donations from a benefactor or benefactress, who would of course in reality have been the child’s biological parent. [Wolfram Aichinger]