A Mother’s Agony.

IV. The Collective Imaginaries

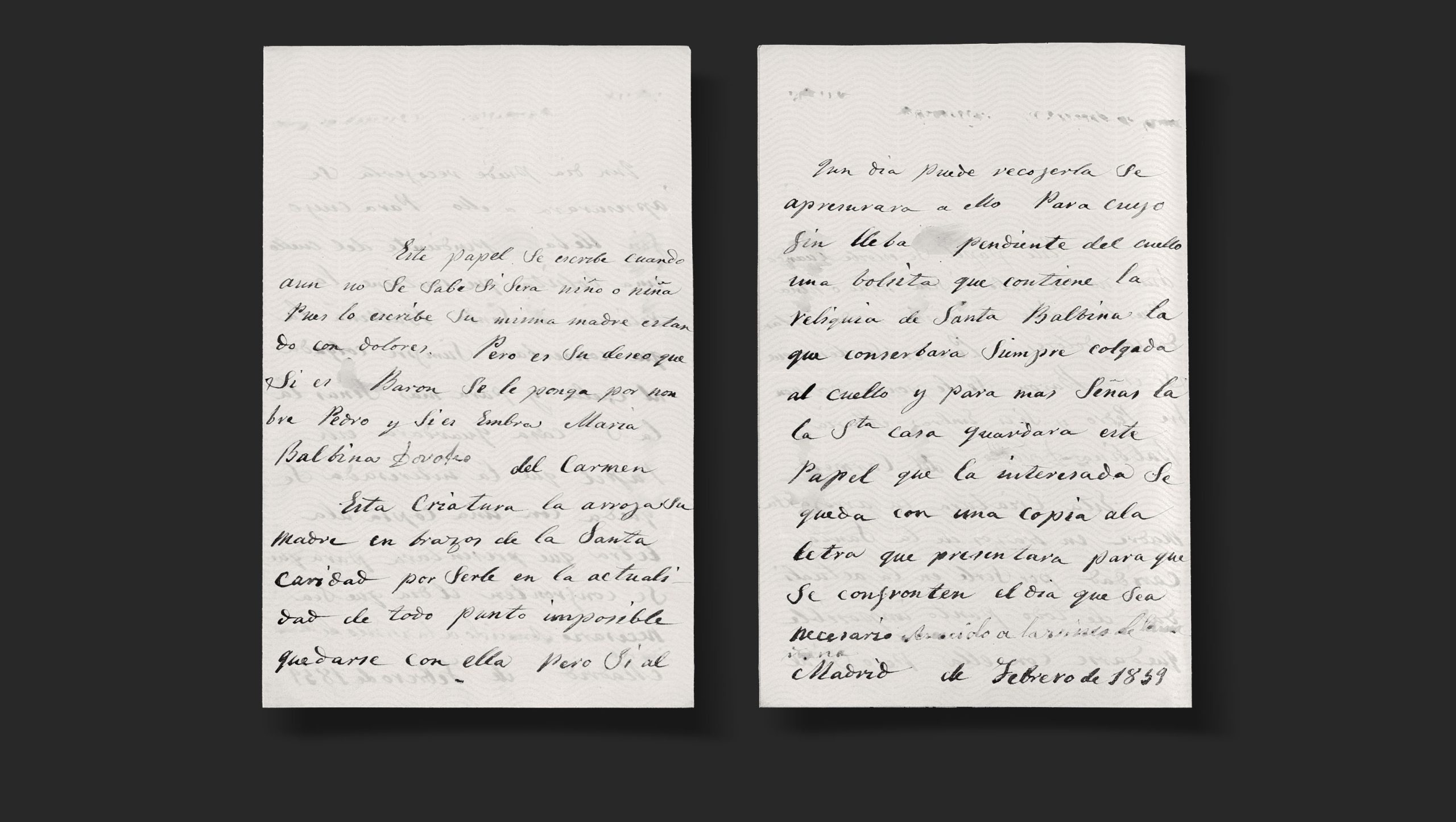

The note pictured here was written by someone who had to hand paper, pen and ink, and who knew how to write fluently, with good handwriting and style. It employs a tone and form of expression quite out of keeping with the brutality of its subject-matter and the faith it places in its personification of institutional beneficence: “This child is cast by its mother into the arms of Holy Charity”.

The motive of abandonment is not given, but it’s surely safe to say that this would have been more a question of honour than of lack of means. The mother undertakes to recover her child as soon as this is “possible”, and to this end commends herself to Santa Balbina and has hung a keepsake of the saint in a little bag around the infant’s neck. Santa Balbina, virgin and martyr, was the daughter of a wealthy Roman family – and Balbina is the name proposed for the child, along with María and Dorotea, in the event it should be a girl. The mother keeps a copy of the letter she is writing so that, the day she is able to reclaim the child, this may be “contrasted” with the original.

The letter was dated February, in Madrid – presumably the fifth or sixth. Especially moving is the phrase squeezed in between the text and the date a few hours later, in the same hand albeit one now visibly weakened: “It has now been born, at five in the morning”.

Many of these notes were composed (or at least so they alleged) by the mothers themselves, and varied considerably in style and length. Often, they would speak of the anguish and despair of a mother unable to care for her child. What is unusual in the letter shown here, and that lends it even greater credibility, is that the mother speaks of her birth pangs, and must therefore be renouncing her motherhood at the exact moment that her body is compelling her to become a mother.

Thanks to the archives of the Inclusa we know how this story played out. The child was born a boy, not a girl. He was given the name Pedro, as proposed by his mother in such an event. His keepsake would give him scant protection, at least during his briefest of passages through the mortal world. He arrived at the Inclusa at a quarter to seven in the morning of February 6, wearing this keepsake. One week later he was taken in by one Matea Bartolomé of Algete, Madrid, who offered the milk she had before fed to her own child, dead at two and a half months on the eleventh of that same February, as certified by the bursar on 12 February 1859. Pedro’s sojourn in his new home would be merely fleeting: he died on the 27th of February of a “catarrh”, as adduced by the local doctor. [Wolfram Aichinger.]