Magic and women in the Classical World

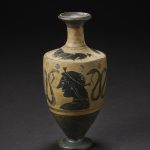

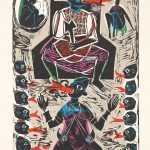

This Temporary exhibition hosted by the Virtual Museum of Human Ecology on magic and women in the Greco-Roman explains some of the divine and other human characters that represented the power of magic in ancient Greece and Rome, as well as the procedures they had to access magic. In the ancient world, the divinities of magic are all female and linked to darkness, especially the goddess Hecate. In addition, several mortal women became famous for the criminal use of their special knowledge, either to take revenge, to fall in love, or fall out of love with their lovers, of which the most famous case is, without any doubt, that of Medea. These special skills may have consisted of technical knowledge (i.e. of plants, potions, ointments, spells, and incantations), usually transmitted from mothers to daughters, as it was associated with women, and linked to the poorest strata of society—an alliance that provided a support network as well as a strategy of resistance to poverty and male oppression. Hence, being a midwife, a healer, and a sorceress was all part of the same profession; and so, the same woman could cure fevers while invoking the forces of the underworld. Prostitution could be added as another activity associated with this world of feminine practices, perceived by men as dangerous, harmful, and repugnant forms of knowledge, the result of the ignorance and misogyny common in the ancient world: although these practices were central and absolutely necessary for the lives of ordinary people, they were relegated, in patriarchal societies, to the margins and to illegality.

As a result of this rejection, ancient literature, masculine and elitist, has transmitted terrible portraits of women like these, such as the Horatian poems dedicated to Canidia and her friends, but also the brutal portrait of the witch Erichtho and her necromantic practices in Lucan’s epic poem Pharsalia, not forgetting the evil sorceress in Apuleius’ Golden Ass, who has the ability to transform herself and her enemies into animals (just like the goddess Circe). All these portrayals have proved fatal to the women’s reputation and are at the origin of important misogynistic stereotypes, such as the femme fatale or the wicked witch in fairy tales. They have also damaged the image of certain animals, such as snakes, dogs, roosters, and rodents, as will be seen throughout the exhibition.

Magic permeated the everyday life of ordinary people, who turned to it when seeking a certain remedy, to protect themselves from the evil eye, and to achieve an effective intervention of a deity in some more delicate matter (love, inheritance, travel). It could be said that the Greeks and Romans were superstitious and tried to defend themselves from the negative gaze (invidiousness) by means of amulets and incantations. Resorting to this magic as a form of physical and psychic protection was cheap; it was also easy and sometimes the only way for normal and (mostly) poor and vulnerable people —children, women, and slaves— to have access to a therapeutic cure. We are facing a historical moment when medical or biological knowledge did not allow a distinction between medicine, religion, and magic; in other words, when magical thinking coexisted with scientific—or perhaps even better—with experimental thinking. At least, they had this resource.

We have put together this exhibition as part of the research project «Marginalia Classica. En los márgenes de la Tradición clásica» of the Madrid Autonomous University (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain, UAM) and the UAM research group Litterae. In addition, three researchers from the Complutense Univerity of Madrid (Universidad Complutense de Madrid, UCM) research group «Textos religiosos de la Antigüedad y del Próximo Oriente» («Texts of Antiquity and the Near East») and researchers from other centers have collaborated in the project. Our scientific interest is focused on the popular practices of Antiquity and the use of classical references in contemporary popular culture.

Rosario López Gregoris, exhibition coordinator, is professor of Classical Philology at the UAM and coordinator of the Litterae research group, member of the Marginalia Classica group. Project hosting this exhibition: PID2019-107253GB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

The following have collaborated in the realization of this Exhibtion: Berta González Saavedra (UCM), Ana González-Rivas (UAM), Alejandra Guzmán Almagro (UB), Paula Avendaño Román (UAM), Carlos Sánchez Pérez (UAM), Mercedes Aguirre Castro (UCM), Begoña Ortega Villaro (U. Burgos), Sara Palermo (UAM), Zoa Alonso Fernández (UAM), Raquel Martín Hernández (UCM), Miriam Blanco Cesteros (UCM), Araceli Striano Corrochano (UAM), María Isabel Jiménez Martínez (UAM), Viviana Diez (U. de La Plata), Luis Unceta Gómez (UAM), Sarah Tolfo (UFRGS, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul) and Lydia Barbosa (UAM).

Further reading:

Campbell, Gordon Lindsay (ed.) (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life, Oxford–New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Charro Gorgojo, Ángel (2004). “Serpientes: ni dioses ni demonios”, Revista de Folklore 283: 3-12.

Christopher A. Faraone (2018). The Transformation of Greek Amulets in Roman Imperial Times. Empire and after. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

Fernández Uriel, Pilar (1996). “Males y remedios II. La evolución de la medicina en la Historia del Mundo Griego”. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Serie II, Historia Antigua 9: 195-219.

Girón Anguiozar, M.ª de Lourdes (2021). “Historia versus realidad: “El patriarcado historiado” y la simbología de la serpiente antes y después del cristianismo”, Revista De Estudios Socioeducativos. ReSed 9: 194-205.

Innes, Alison (2011). “To Help or to Harm: Female Practitioners of Pharmaka in Ancient Greece” (pp. 56-66). In April Anson (ed.), The Evil Body, Leiden: Brill.

Judge, Shelby (2023): “‘Men make terrible pigs’: Teaching Madeline Miller's Circe and the New Feminist Mythic Archetype”, The Classical Outlook 98/3: 108-118.

Lecouteux, Claude y Boyer, Regis (1999): Hadas, brujas y hombres lobo en la Edad Media: historia del doble. Medievalia 6. Palma de Mallorca: José J. de Olañeta

Madrid, Mercedes (2009). “Medea: hechicera y madre asesina”, Dossiers Feministes 13: 29-44.

McIntyre, Gwynaeth & McCallum, Sarah (2019): Uncovering Anna Perenna. A Focused Study of Roman Myth and Culture, London–New York: Bloomsbury.

Molina-Venegas, Rafael & Verano, Rodrigo (2024): “The Quest for Homer's Moly: Exploring the Potential of an Early Ethnobotanical Complex”, Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 20/11.

Olson, Kelly (2009). “Cosmetics in Roman Antiquity: Substance, Remedy, Poison”, CW 102: 291-310.

Pérez González, Jordi (2017). “Elaboración y comercialización de perfumes y ungüentos en Roma. Los unguentarii”, Revista de Estudos Filosóficos e Históricos da Antiguidade 31: 81-110.

Piranomonte, Marina (2010) “Religion and Magic at Rome: The Fountain of Anna Perenna” (pp.191-214). In Richard L. Gordon & Francisco Marco Simón (eds). Magical Practice in the Latin West, Leiden–Boston: Brill.